Atrocity, curiosity, tragedy, travel: Battlefield tourism in the Solomon Islands

Dark periods of history evoke strong emotions, particularly among those with close connections to participants. As documented by Stephen Pratt and his colleagues, cruise tourists who chose to join a shore tour of World War II battlefield sites, museums, and memorials on Guadalcanal did so for a variety of reasons and felt a range of positive and negative emotions.

Meanwhile, Solomon Islanders weigh up the opportunities and responsibilities associated with this ‘dark tourism’ niche.

It’s a “Good Tourism” Insight.

[Thanks to Joseph M Cheer for inviting Prof Pratt to write a “GT” Insight.]

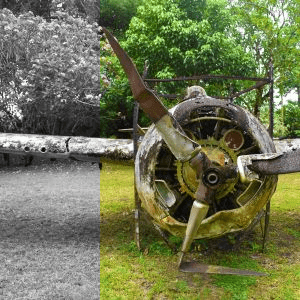

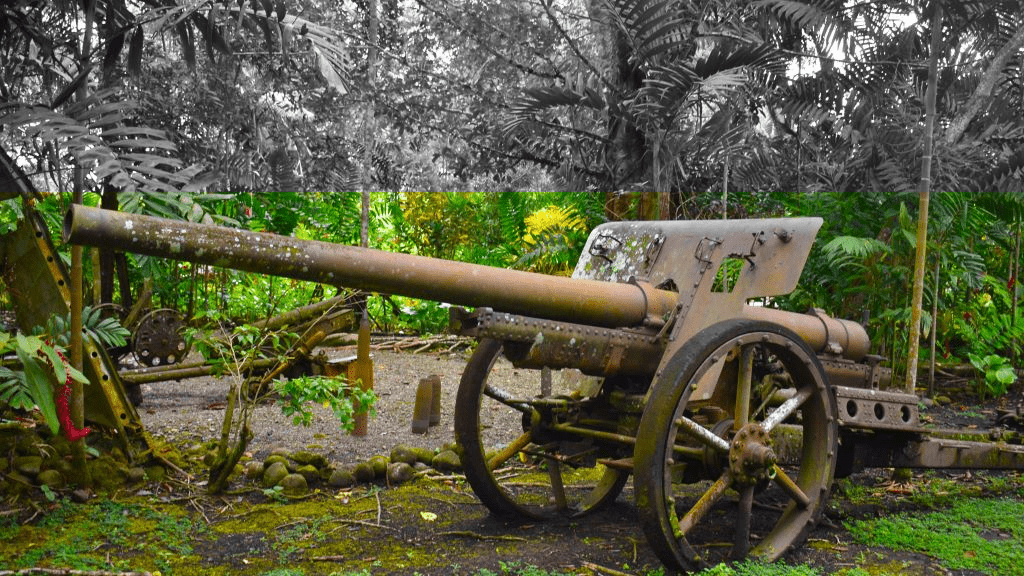

World War II left indelible scars across many countries, not only emotionally and psychologically, but also physically. Battles were fought throughout the world during that terrible war, including in the South Pacific. Military forces left artillery and other war debris strewn across landscapes and the ocean floor.

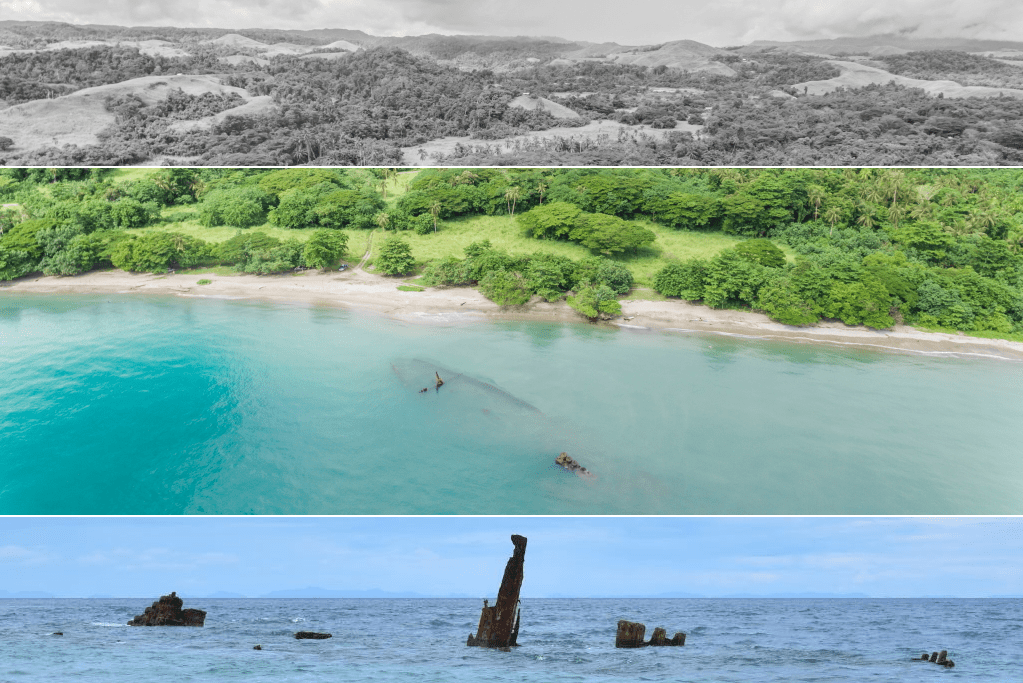

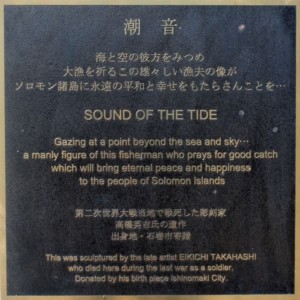

The Battle of Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands, was one of 10 conflicts fought between the Japanese and the Americans during World War II. The physical scars it left behind include war memorials for both sides, plaques, monuments, and the wreckage of ships and aircraft.

Seventy years after the end of World War II, some in the Solomon Islands see potential in the World War II battles that took place there as a way to help people — local and foreign, young and old — accept and learn from the past.

They point to how the battlefield sites provide military enthusiasts and historians, war veterans and their descendants, and even local school children with, variously, a tangible reminder of death and sacrifice, a sense of closure, an education about past wars, and a motivator for future peace.

At the same time, a related tourism niche, dubbed ‘dark tourism’ by some, has the potential to be a source of economic development for the local community.

Mixed emotions among tourists

While dark tourism attractions have long enticed visitors to sites associated with death, suffering, or the macabre, this doesn’t necessarily mean the experience of visiting these sites is associated with all negative emotions.

Previous research has shown that visitors to dark tourism sites experience strong emotions that are both negative (anger, hatred, vengeance, fear, horror, depression, sadness, defeat, loss, humility, and empathy) and positive (awesome, amazing, memorable, peaceful, hope, love, pride, fascination, interest, touching and gratitude).

Also see Bjørn Z Ekelund’s “GT” Insight

“In the eye of the beholder: How to create valuable tourism experiences”

Dawn Gibson, Eileen Yai, and I recently conducted research among cruise ship passengers who toured the Battle of Guadalcanal sites in the Solomon Islands as part of a shore tour. Seven sites associated with the Battle of Guadalcanal were on their itinerary. These included two War Memorials (Japanese and American), the National Museum, and two open-air museums (Betikama Museum, Vilu Museum) that exhibit artifacts from the Battle of Guadalcanal such as the remains of planes, submarines, tanks, and other artillery. There were also two battlefield sites: Bloody Ridge (Battle of Edson’s Ridge) and Alligator Creek (Battle of the Tenaru).

Our survey asked the tourists about their main motivation for attending the tour. About 25% indicated that they attended the tour for the rich history; ~20% wanted to visit famous WWII battle sites; another ~20% wanted to deepen their knowledge about the War in the region. The remainder joined the shore tour without clear intent; mainly simple curiosity or as a distraction for the day.

The tourists described a range of emotions when visiting these dark tourism sites. The most common negative emotions included sadness, loss, and defeat. The positive emotions most commonly cited included surprise, amazement, and awe. Some cruise tourism visitors experienced the primary emotions of both sadness and surprise. Others felt optimism, serenity, and love. Still others experienced multiple emotions.

The attractions varied in terms of the strength or mix of emotions they evoked. The open-air museum of Betikama, for example, caused some cruise tourism visitors to feel awe; others to be contemplative and quiet. Mirroring the different perspectives of the adversaries, the American War Memorial evoked positive feelings of victory or awe, while the Japanese War Memorial was more likely to call up negative feelings of loss, defeat, and sadness.

Mixed views among locals

We also surveyed local Guadalcanal community members and Solomon Islands tourism stakeholders. They have mixed views about the extent to which battlefield tourism can be developed for the betterment of locals.

Also see the “GT” Insight by Movono, Scheyvens, and Auckram

“What do the people want? Reimagining Pacific Island travel & tourism”

Most local respondents were unfamiliar with the term ‘dark tourism’ although they had visited the WWII sites and had grandfathers who fought during the war.

The Ministry of Culture and Tourism is the Government body that implements policies for the tourism industry in the Solomon Islands. At present there are no government policies related to the preservation of WWII sites and relics.

Tourism Solomons is the primary destination marketing body. There is little strategic focus on battlefield- or WWII-related dark tourism development.

What is clear is that the numerous stakeholders need to work together to provide a rich, authentic and educational experience that benefits residents. The key challenge to developing WWII sites for that will be getting the support of the local community in which there are different attitudes towards the preservation of WWII relics.

Some local residents see the remnants of war as an educational tool to include in history studies at school so that children can learn about the Second World War and appreciate the importance of preserving these relics. Others question why they should protect WWII relics, feeling that they represent the history of Japan and America and not the Solomon Islands.

Solomon Islanders generally seem to be quite fragmented on whether or not to develop the battlefield tourism niche further. Widespread and inclusive dialogue among them will be the first step in moving forward. Now would be a great time to start.

What do you think? Share a short anecdote or comment below. Or write a deeper “GT” Insight. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

Featured image (top of post): Kinugawa Maru, the Japanese supply vessel wrecked at Bonege ii Beach, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. Aerial image by Gilly Tanbose (CC0) via Unsplash. Sea level image by author.

About the author

Stephen Pratt is a professor and deputy head of the School of Business & Management at the University of the South Pacific, Fiji. He is also a visiting professor at the Center for Tourism Research, Wakayama University, Japan. Prof Pratt’s research interests include sustainable tourism development — particularly tourism’s economic, sociocultural, and environmental impacts in small island states — and film tourism. Stephen is also a co-creator of The Travel Professors, a YouTube channel, where he’s known by the nickname Stevo.