In praise of holiday Fordism & why it’s misanthropic to malign mass tourism

Nearly everyone wants to escape their everyday and take a holiday, including working people with small budgets and limited time. Does that mean they, and those who cater to them, are terrible people?

Jim Butcher doesn’t think so. In his third “Good Tourism” Insight, Dr Butcher paints mass tourism in a progressive light and defends the much-maligned mass tourist.

Fordism refers to modern manufacturing that leverages the technology of the production line and benefits from economies of scale and scope. In this context, Henry Ford himself wrote of the Model T, the exemplar of the 20th century’s earliest production lines:

“Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black.’’

Ford, H (1922) “My Life and Work”

Colour didn’t matter. The Model T was affordable to so many more people than previous motor cars had been. Thus mass consumption, including more colour options, naturally followed from mass production.

This hardly sounds very touristy. As tourists, we want to explore our individuality and ‘find ourselves’. Yet the principles of Fordism have long been applied to tourism. And, far from a stultifying sameness, they have contributed greatly to individual freedom.

Mass tourism: Broadening horizons since the 1840s

‘Holiday Fordism’, or mass tourism, really precedes Ford. It dates back to the early pioneers of tourism, such as Thomas Cook.

From the 1840s Cook offered domestic holiday packages to Britain’s new and expanding market of working class people who had a little disposable income. Ever since mass tourism has grown on the efficiencies of economies of scale and scope, which are realised by setting up to serve large markets of potential travellers affordably.

Fordism characterised international tourism too. It became for many in Europe the means by which they travelled abroad for the first time, and regularly thereafter. The business model kept prices low and contributed to the democratisation of leisure travel.

After the second world war the jet engine became the key technological innovation shaping the travel & tourism industry. While aircraft had already linked the source markets of northern Europe to the Mediterranean, jet engines could propel larger aircraft faster. Large and fast aircraft meant greater scope for economies of scale.

In the 1970s independent charter airlines, boosted by capital from the shipping industry, pioneered the ‘back to back’ charter (seen as innovative in its time).

For British tourists the package price for a week on the French Riviera, the Costas, the Balearics, or a Greek island, became closer to that of a week in Blackpool, Bognor, or Brighton. For many the Med proved preferable. The economic and social transformation of poor fishing villages was one result. On the whole, hosts and tourists benefited.

The French Accor group is also illustrative of the way Fordism and standardisation enabled growing numbers of people to travel for leisure. Accor pioneered low cost, highly standardised hotels, situated outside town centres on arterial routes to lower costs yet maintain access.

Initially intended for the growing band of car driving travelling salesmen, Accor’s hotels became popular with budget-minded leisure travellers from the 1970s onwards. It became easier for French people to visit their friends and relatives who lived in towns and cities away from the principle tourism destinations. Counter-intuitively, hotel standardisation led to more individual choice.

Also see Jim Butcher’s “GT” Insights

“Tourism’s democratic deficit” and

“Why tourism degrowth just won’t do after COVID-19”

Holiday resorts can be thought of as Fordist too. They encapsulate scale economies, mass standardised transit and accommodation, and are shaped around convenience, access, and consumer desires. There is a pejorative undercurrent in some contemporary commentaries on such places, especially Mediterranean resort towns such as Torremolinos, Benidorm, and Faliraki. They have become bywords for damaging mass tourism among tourism’s ‘ethical’ critics.

The Italian resort of Rimini is illustrative of the fact that the growth of mass tourism on the Mediterranean was not simply a matter of ‘more of the same’. Since 1843, and the founding of its first bathing establishment, Rimini has been a beach resort town. It has had to adapt to changing circumstances to variously thrive or survive ever since.

Rimini’s initial development as a resort in the 19th century was innovative, exciting, and of its time; a gathering place for elite wealthy socialites. By the 1950s and 60s it was a leader in family beach holidays. In response to stagnation in the late 1960s, when Spain and Yugoslavia started offering cheaper alternatives, Rimini reoriented itself towards a younger market so that by the 1970s and 80s it was the trendy disco capital of Italy. In the 1990s new ‘MICE’ products served conferences and trade fairs, and new theme parks attracted families once again.

My mother travelled to Rimini in the 1960s. For her and her Glaswegian friends, this was their first destination outside the UK, and their first taste of another culture and language. For them, Rimini was distant, exciting, and exotic.

Is mass tourism akin to ‘comatose consumerism’?

Yet Fordist mass tourism has been criticised in cultural terms. In the decades after the second world war Frankfurt School thinkers identified Fordism with a dumbed down, ‘produced’ culture that stood in the way of the masses understanding and acting on their class interests.

More recently this sentiment has been echoed, shorn of the class politics, by academics and campaigners seeking to reign in what they see as tourism’s excesses. For example, one recent account refers to consumers consuming in “robot like fashion”, whilst another to the “comatose consumerism” of the holidaymaker.

In recent decades tourism has moved towards niche tourism brands that seek to appeal — sometimes self-consciously — to tailored, ethical, and individual preferences. These niches are often presented not simply as matters of individual wants but as linked to ethical lifestyles. Not infrequently, they extol the virtues of the person who would choose to take such a holiday.

Mass tourism for the unthinking masses, and niche travel for the culturally and environmentally aware, remain all too common tropes in both academic and popular commentary on tourism. Travel editor Anthony Peregrine has a point when he writes:

“Disdaining tourists is the last permitted snobbery, a coded way of distancing oneself from the uncultured classes.”

‘The Telegraph’, March 26, 2019

These caricatures betray a certain dehumanisation of the mass tourist through the removal of their cultural agency; a recurring theme in portrayals of mass tourists through history. However, critics of holiday Fordism today adopt a different tone to that of the cultural elites of an earlier period.

Back in the 19th century the loathing of the pleasure-seeking masses was unguarded. The Victorian diarist Reverend Francis Kilvert famously wrote:

“Of all noxious animals, the most noxious is a tourist. And of all tourists the most vulgar, ill-bred, offensive and loathsome is the British tourist.”

Plomer, W (ed) ‘Selections from the Diary of the Rev. Francis Kilvert’

Today it is more likely that mass tourists are portrayed as unthinking conformists, lacking individuality, and in need of enlightenment rather than condemnation. Their lack of thought is deemed to have ethical implications, as, without correction, they may damage the cultures and environments they visit. In this way, the widespread advocacy of ethical tourism since the 1990s — referred to by one academic as ‘the moral turn in tourism’ — takes as its object of criticism the Fordist mass tourist.

Tourism choice is something to celebrate

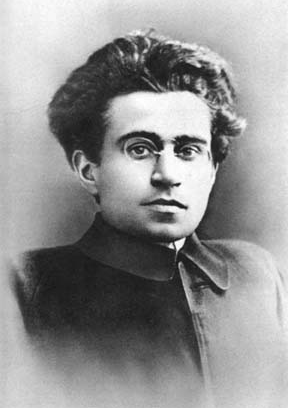

By contrast, in the 1930s, the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci discussed Fordism as a progressive development. He saw the potential for it to liberate the majority from a life of toil. (He was on the side of my mother and her companions.)

Gramsci wrote of the liberating character of mass production for individuals in a way that is prescient for discussions about tourism today:

The term “quality” simply means …. Specialisation for a luxury market. But is this possible for an entire, very populous nation? …. Everything that is susceptible to reproduction belongs to the realm of quantity and can be mass produced … if a nation specialises in “quality production”, what industry provides the goods for the poorer classes? … The whole thing is nothing more than a formula for idle men of letters and for politicians whose demagogy consists of building castles in the air.

Gramsci, A (1929 – 1935) on Americanism and Fordism

It is notable that Gramsci refers to ‘quality’ in inverted commas, taking up critics who see something intrinsically lesser in mass production. ‘Quality’ is the adjective often adopted today to refer to tourism that is promoted as personalised, ethical, and smaller scale.

However, non-mass tourism niches and independent travel depend upon the gains of Fordist production too. Making moral distinctions between mass and quality is little more than pious moralising about others’ choices.

Jet technology, economies of scale and scope, and economic growth in general have underpinned the geographical range of tourism opportunities through which an individual can cultivate their identity.

Today the highly standardised budget airlines offer the opportunity for many more to travel to a wider variety of places, and to broaden their experience of the world. As AirAsia puts it in its slogan: “Now everyone can fly”.

The Fordist ‘holiday from the assembly line’ sounds pejorative, but it is in fact highly liberating. It widens choice and enables countless possibilities. There is nothing wrong, and much to celebrate, in being able to seek tranquillity at a yoga retreat atop a Pyrenean mountain, or to go in search of gorillas in Rwanda. But associating these new niches with a higher moral purpose, or a more evolved individual, is unjustified.

Every ethical niche depends upon the technology and wealth borne of our industrialised society. Whilst culturally some may seek to differentiate themselves from the masses via their leisure choices, it is Fordist mass production that has enabled those choices, and the growth in tourism for all tastes. That’s something to celebrate.

Agree? Disagree? What do you think? Share a short anecdote or comment below. Or write a “GT” Insight of your own. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion about travel & tourism because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

Bibliography

Butcher, J (2003) The Moralisation of Tourism. Routledge, London.

Gramsci, A (1929 – 1935) on Americanism and Fordism. In: Hoare, Q (ed) (2005) Selection from the Prison Notebooks. Lawrence and Wishart, London.

Segreto, L; Manera, C; and Pohl, M (editors) (2009) Europe at the Seaside: The Economic History of Mass Tourism in the Mediterranean. Berghahn Books, New York.

Featured image (top of post): Image by Kindel Media (CC0) via Pexels.

About the author

Jim Butcher is a lecturer and writer who has written a number of books on the sociology and politics of tourism. He is now working on a book about mass tourism. Dr Butcher blogs at Politics of Tourism and tweets at @jimbutcher2.