Oh, Canada: Reconciliation via Indigenous storytelling, dignity, and ‘dark tourism’

Can tourism — ‘dark tourism’ — and the storytelling that it facilitates help Canada and Canadians reconcile their past and look forward to a brighter, more united future?

Kelley A McClinchey and Frédéric Dimanche explore these themes in this “Good Tourism” Insight. [You too can write a “GT” Insight.]

Contents

A revelation of truth

For more than 150 years, Canada’s Indigenous children were isolated from their families and sent to residential schools to remove their cultural identity and assimilate them into Canadian society.

But it wasn’t until 2015 that the world heard their stories, when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report was published.

With 94 Calls to Action, the report detailed the account of what happened to Indigenous children who were physically and sexually abused in government schools, and where an estimated 3,200 children died from malnutrition and diseases resulting from poor living conditions.

To date, hundreds of confirmed or suspected unmarked graves have been identified at sites of former residential schools in Canada. Of 139 residential schools, only 11 have been investigated so far.

Many survivors say the investigation is moving too slowly.

The religious institutions that managed those sites remain largely silent about their devastating legacy.

A journey towards reconciliation

The 94 Calls to Action in the TRC report continue to urge all levels of government — federal, provincial, territorial, and Indigenous — to work to change policies and programs to repair the harm.

Canadians also need to acknowledge the truth and move towards reconciliation.

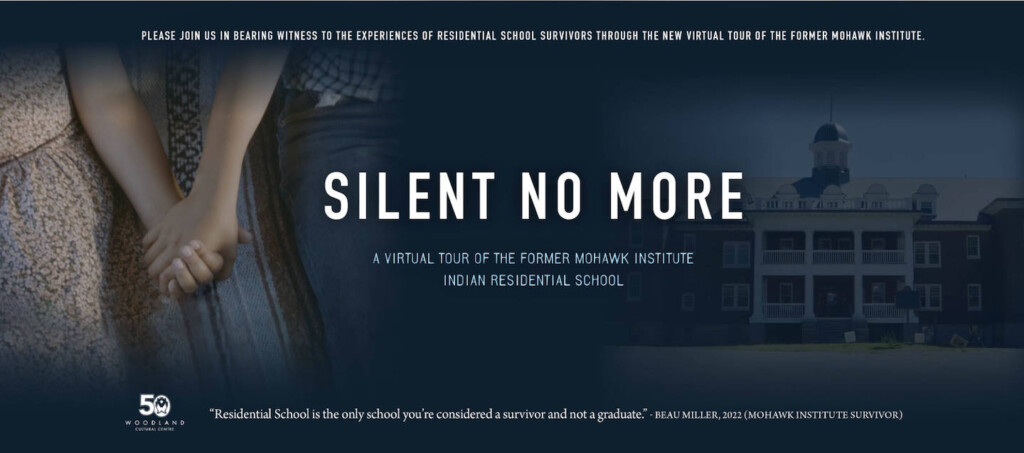

There may be an opportunity for Canadians and Indigenous peoples to move forward together by listening to these stories and visiting the places where this often-forgotten history took place.

Many of the residential schools have been destroyed or are in extreme disrepair, left standing as a memory of a difficult past.

While the preservation and promotion of spaces and memories is a delicate issue, there are examples of where it has been successful at maintaining memory, meaningful learning, raising deep emotions, and invoking closure.

Tragedy and disaster have had to be approached with sensitivity relating to the trauma and memory associated with the Holocaust and the sites of the enslaved in West Africa, the Caribbean, and the USA.

How can we bring forward the truth and reconcile with our difficult heritage?

Don’t miss other “GT” content from the Americas

Storytelling and ‘dark tourism’

One way may be through ‘dark tourism’, a niche, yet prominent form of heritage tourism associated with sites of death and disaster.

Effective places of dark tourism (e.g., Auschwitz, Hiroshima Peace Memorial, 9/11 memorial) are designed to create meaningful affective responses.

While trauma exists at dark tourism sites for those closely affected and for those who visit, the benefit here is the healing power of storytelling.

Indigenous power can be reclaimed through the sharing and telling of alternative stories. While storytelling can invoke deep emotions that may be negative in connection to dark tourism sites, dark tourism can allow Indigenous peoples to tell their own stories and make these places of truth and reconciliation rather than tragedy.

Co-creation of these sites could contain storytelling components, to relay the history in a way that is appropriate and truthful for the community.

Don’t miss the “GT” Insight by Stephen Pratt: ‘Atrocity, curiosity, tragedy, travel: Battlefield tourism in the Solomon Islands’

Through darkness comes healing and hope

There is power in storytelling as there is in tourism. Both can be used for good, for building peace, and to leverage a counter-narrative to generate power through hope and healing and reconciliation.

There are varying moral considerations and motivations for dark tourism, but there is often compassion and care communicated through delicate co-management practices, co-creation, and consultation with local communities.

There are some Indigenous sites where this is already taking place, such as St. Eugene Golf Resort and Casino on the Kootenay Indian Residential School site. Sophie Pierre, former chief of the St. Mary’s Indian Band, played an integral role in turning the building into a tourist destination.

When ownership of the building transferred to the five Indigenous Bands in the region, some wanted to tear it down, hoping that it would make the hurt go away. But former Chief Pierre was inspired by Elder Mary Paul, who encouraged the community to take back what they’d lost in the St. Eugene Mission.

In addition, with very few residential school buildings still standing today, the walking tours of the Shingwauk site at Algoma University are increasingly important as an experiential learning tool.

Hope can be a way to focus on the educational components of tourism, on the memory work needed to learn and bring an alternative story of the place.

Don’t miss other “GT” content tagged ‘Culture, cultural heritage, & history tourism’

A 95th Call to Action: Work together

Five years after the publication of the TRC report, Wilton Littlechild, a lawyer and Cree chief who is a residential school survivor, said that if he were able, he would have added a 95th Call to Action saying: “We must work together.”

TRC Chair Senator Murray Sinclair stated: “We need to ensure that we never, ever let Canada forget what they have done, and the situations that we are now facing that are the responsibility of this history.”

Many of these residential school sites are in dire need of repair. Opportunities to preserve them as places of truth may disappear. Just as Auschwitz is vital to telling the story of the Holocaust, so to these residential schools are vital to ensuring that Indigenous voices are heard and for Canadians to keep hearing the truth.

Truth is painful; memories still ache, but dark tourism can be a significant tool in addressing the pain of a colonial past and moving towards reconciliation together.

What do you think?

Share your own thoughts about ‘dark tourism’ and/or Indigenous tourism in Canada in a comment below. (SIGN IN or REGISTER first. After signing in you will need to refresh this page to see the comments section.)

Or write a “GT” Insight or “GT” Insight Bite of your own. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism, because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

“GT” doesn’t judge. “GT” publishes. “GT” is where free thought travels.

If you think the tourism media landscape is better with “GT” in it, then please …

About the authors

With a PhD in human geography specialising in tourism, place-making, and sustainability, Kelley A McClinchey is a lecturer at Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada.

Dr McClinchey is interested in how hospitality, tourism, and events contribute to sustainable livelihoods and resilient communities. And she values the use of personal stories and narratives in understanding tourism in diverse places and contexts.

Kelley loves to hike wild trails, stroll city streets, and sit at cafés wondering who else in the past has witnessed changing heritage landscapes.

Frédéric Dimanche is the Director of the Ted Rogers School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly known as Ryerson University), Canada.

After earning his PhD at the University of Oregon, USA, Dr Dimanche worked in New Orleans, USA and then Nice, France before returning to North America.

Frédéric has multiple research interests that range from tourist behaviour to destination competitiveness.

He is an avid traveller and loves the outdoors.

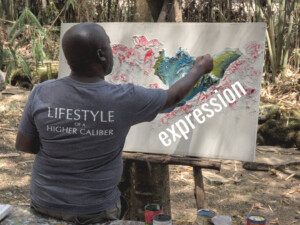

Featured image (top of post)

Cedar Lake Ranch. Photo by Taylor Burke, courtesy of the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC) Manitoba.