Ecotourism for the masses, not the elite classes!

‘Ecotourism for the masses, not the elite classes!’ is a slogan you’re unlikely to hear at a protest any time soon.

Sudipta Sarkar argues for an urban ecotourism for the masses that looks far beyond Western debates for inspiration.

It’s a “Good Tourism” Insight initiated by Tourism’s Horizon, a “GT” Insight Partner.

[You too can write a “GT” Insight.]

Ecotourism carries a variety of associations: Niche, small-scale, low-intensity travel; welfare for the visited; disapproval of human interferences in nature; and ecocentrism (valuing the natural world over and above human interests).

It assumes a certain moral authority in debates around tourism, especially vis a vis mass tourism. But this is not uncontested.

Ecotourism is criticised too: For some, ecotourism greenwashes commercial interests; that it is a ‘Trojan Horse’ that will eventually unleash damaging mass tourism.

Still others take a different line: Martin Mowforth and Ian Munt see ecotourism as a conscience-salving activity for the middle classes, while Jim Butcher accuses ecotourism advocates of denying modernity to the poor.

Most agree that local perspectives from the ‘global south’ should be paramount.

Locals can be aspirational. Host communities can desire modernisation. In some cases they can be resistant to development and industrial/technological progress.

Many in Western academic circles have elevated the latter view. But this ignores the former; that the masses of the global south also have material needs and wants, including a desire to travel, and a right to fulfil them.

Read other “Good Tourism” content tagged with ‘Ecotourism and nature-based tourism’

Romantic ecotourism

Part of the problem lies in a Western view of the human-nature relationship, which can be traced back to the age of Romanticism in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

Romanticism was an artistic and literary movement that saw in nature sublime beauty and an affirmation of humanity; a moral and spiritual counterpoint to the rationalising tendencies of modernity that crushed the individual.

Several literary works came out of that era that were based on the philosophical foundations of Romanticism.

There was a darker side to Romanticism: As it prevailed as a cultural movement at home, British colonialists in India were responsible for decimating a wide range of species in formerly pristine ecosystems.

Romanticism also fed into a European view of Africa as a repository of wild, untamed nature, a view that incorporated the racial thinking of the period.

In recent times, a radical-activist perspective has provided further impetus to this ‘austere’ view of our relationship to the natural world, and this is evident in some of the writing about ecotourism in Western academia.

Morally superior ecotourism

Whereas ‘ecotourism’ as a term has lost its sheen, its assumptions about the destructive character of ‘mass tourism’ and the need to foster only localised ecotourism development has been widely adopted by the ‘social justice’ lobby.

The social justice view is that mass tourism is unsustainable in its entirety and unwaveringly destructive of nature, society, and economies.

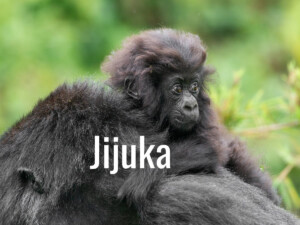

The legacy of ecotourism, manifest in numerous nature-based products, is the continuation of elitist forms of niche travel. For example, gorilla tours in Rwanda cost up to USD 7,000. Ecotours in Malaysian Borneo are priced as high as USD 1,600.

These are low-volume luxury services for the few. While such tours can help to protect endangered flora and fauna, and support conservation and local community welfare, they perpetuate class discrimination in tourism consumption.

Such elitist forms of ecotourism often attract consumers from wealthy Western countries; disproportionately from the racial majority in these societies.

The Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan, for which many in the West have developed a fetish for its scaled down (‘low volume high yield’) tourism policy, is yet another example of elite niche, not necessarily eco‑, tourism consumption that makes itself accessible to mostly wealthy Western visitors.

Either way, ecotourism is a niche for the rich. Fair enough, you might say; supply and demand dictates price and most of us aspire to afford luxury products of some sort.

The problem is that ecotourism, in the Western conception of it, is self-consciously styled as morally superior to mass leisure pursuits.

Humanist ecotourism

I would argue that ecotourism needs to be refounded on a humanist basis that does not rhetorically or practically pit the appreciation of nature against the material interests of the mass of humanity.

Inspiration for such a change may be found in an understanding of ecotourism derived from East Asia; ideas and philosophies that lead us towards a view of nature that is sympathetic, not antithetical, to the masses.

In the Chinese notion of Shengtai Luyou (生态旅游; shēngtài lǚyóu; ecology travel) the wellbeing of visitors gets equal priority with nature.

Human arts and spiritual artefacts are compatible with nature. People are less likely to be seen as players in a zero-sum game against the natural world.

Then we have the Japanese idea of Shinrin Yoku (森林浴; shinrin’yoku; forest bathing). This involves nature-based therapeutic activities, spending quality time with friends and family members, temple visits, and meditation.

Engagement with nature becomes very humanistic. It is about people, their values, and their relationships to each other, as well as to the natural world.

The philosophies of Zen Buddhism and Confucianism stress the Unity of Man and Heaven; the Trinity of Heaven, Earth and Humans; and Creative transformation.

- The Unity of Man and Heaven deems all constituents of Earth (including humans) as one single entity.

- The Trinity of Heaven, Earth and Humans are the three elements of the cosmos, within which humans are considered as offspring of earth and heaven.

- Creative transformation relates to the harmonious amalgamation of natural and human aesthetic elements in nature, augmenting its spiritual dimension.

These philosophical attempts to bring nature and humanity together are not unique to Asia. For example, in the second half of the 19th century socialist William Morris pioneered the Arts and Crafts Movement which tried to bring the beauty of nature right into the urban environment inhabited by the industrial proletariat.

Nonetheless there is a dissonance between influential Western and Eastern perspectives about the role of humans in nature.

From an Eastern cultural perspective the relationship is not dominative but constitutive; nature as a spiritual setting in which humanity belongs, rather than one it is in tension with. This in turn leads to an appreciation of nature — the motivation for ecotourism — that is for, not against, mass society.

The elitism observed in ecotourism for the few, as advocated in the current Western discourse on sustainable tourism, underscores the need for something rather different; an ecotourism for the masses; an urban ecotourism.

Also read Sudipta K Sarkar’s “Good Tourism” Insight ‘Wild urban spaces: Rethinking ecotourism as a mass tourism product’

Ecotourism for the masses: The case for urban ecotourism

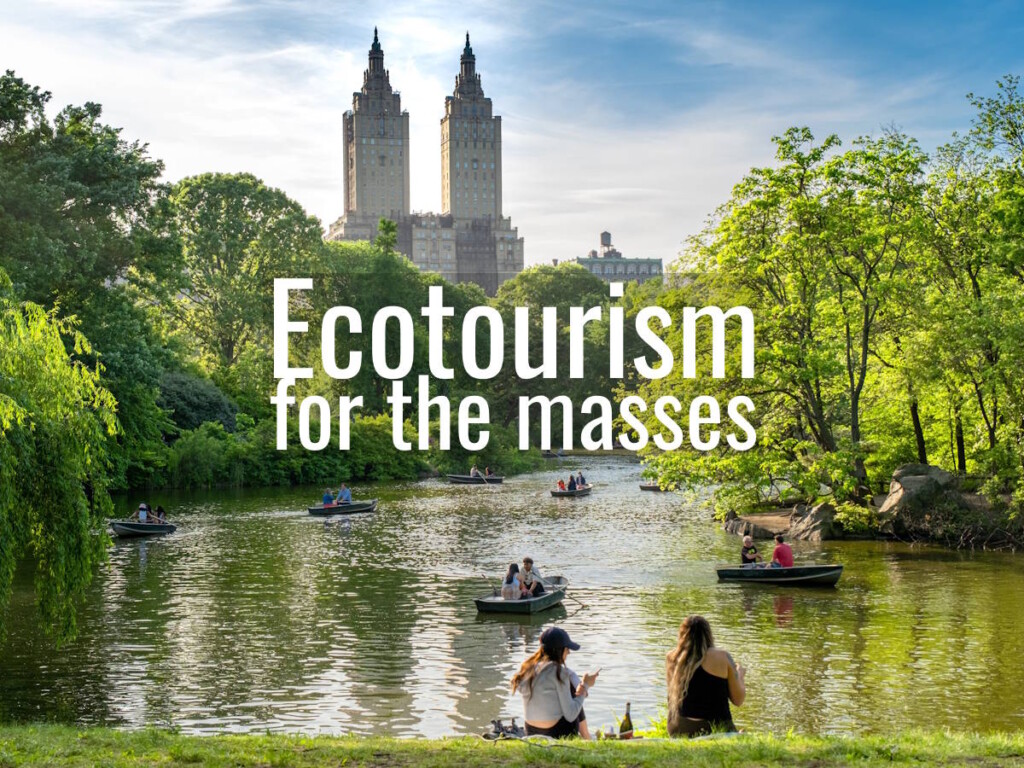

Urban ecotourism involves nature-based recreation within, and within easy reach of, cities; offering visitors and residents — particularly from marginalised groups and with accessibility needs — an opportunity to sample nature and fulfil their therapeutic, recreational, and social needs at relative ease and low cost.

Natural ecosystems that are close to urban areas tend to be relatively adaptable and resilient compared to rural, remote areas with fragile ecologies. This is by virtue of enduring urban development over considerable periods of time.

Mass travel and non-seasonality, being inherent to urban ecotourism, can render economies of scale that justify robust investments in the protection and conservation of natural systems in and around cities.

Urban ecotourism sites that are well-connected by mass transit systems score another ‘sustainability’ point in their favour.

Urban ecotourism sites, particularly in Asian contexts, also permit the integration of aesthetic structures that can enhance the recreational, artistic, spiritual, and therapeutic value for the masses.

To counterpose ‘ethical’ ecotourism to mass tourism, when we live in a mass society that has brought plenty of progress, makes no sense, is elitist, and is self-defeating.

Moreover, the assumption that the welfare of the visited solely matters, not that of the visitor, is also one-sided. Wherever they are from, tourists are also workers with families, aspirations, needs, and wants.

Regardless, the restorative and ecological benefits of the natural areas where many of us live — in cities — can be a basis on which emotional solidarity between host, visitor, and nature can be achieved for a truly responsible and sustainable tourism future.

Agree? Disagree? Share your own thoughts in a comment below. Or write a deeper “GT” Insight. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism, because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

“GT” is where free thought travels.

This “Good Tourism” Insight was initiated by Tourism’s Horizon: Travel for the Millions, a “GT” Insight Partner. Tourism’s Horizon is “a diverse range of people, from academia, journalism, and industry who share a love of holidays and a desire to optimistically explore the economic and cultural advantages of mass tourism”.

Featured image (top of post): Is Central Park in New York an example of ecotourism for the masses? Image by Harry Gillen (CC0) via Unsplash.

About the author

Sudipta K Sarkar is a senior lecturer in tourism management at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, UK. With a PhD from the School of Hospitality & Tourism Managment at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Dr Sarkar has been an educator since 2001 in Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, South Korea, and the UK.

Sudipta has authored and co-authored book chapters, journal articles, and conference papers in the areas of socialisation among ecotourists; sustainability and social media; urban ecotourism for the masses; technology and sustainability; tourism education; and peace and gender issues. He has also received accolades from higher education and student bodies for his contributions to culinary entrepreneurship and tourism.