Where is the line between cultural explorer and voyeur? The ‘Batwa Experience’

Where is the line between cultural exploration and exploitative voyeurism while travelling among indigenous peoples?

In this “Good Tourism” Insight, Gavin Anderson explores the danger and promise of travel & tourism’s involvement with indigenous people through the lens of his recent work with the Batwa of southwest Uganda.

[You too can write a “GT” Insight.]

I first met the Batwa, the indigenous forest people of central Africa, in the early 1990s as a traveller camping in the Semliki Valley of Uganda.

I encountered the spectacle of overland trucks of tourists arriving to spend an hour with the “Pygmy forest people”; spending money (on photos and trinkets) that was subsequently spent on exploitatively expensive alcohol in the village shops. The sight made me avoid the emerging ‘Batwa Experiences’.

When I returned to Uganda as a development worker in 1997, I seldom visited Twa communities. I lived there for nine years, yet my work did not involve the Batwa at all, and I continued to feel that tourism’s interest in them was morally questionable.

Don’t miss other “Good Tourism” content about destinations in Africa

In 2023 I returned to Uganda to finalise plans for a trekking journey through the lakes, mountains, forests, and villages of southwest Uganda. The trip would take us through the Echuya, Mgahinga, and Bwindi forests that had been the ancestral homes of the Twa.

I came with the experience of working with other indigenous peoples in tourism; particularly the Dolpo-pa, a Tibetan people in the high Himalayan valleys of northwest Nepal. I had directly experienced how travel & tourism that works with local indigenous people can benefit cultural preservation, provide income to communities, and give travellers a worthwhile experience.

A key question I had was: How could something similar be done with the Batwa of Uganda who had firstly been dispossessed by conservationists and government, and then disrespected and demeaned by the tourism industry?

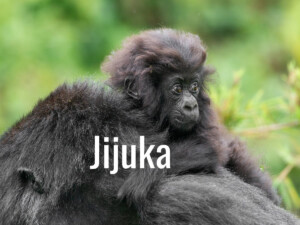

“Twa” is the ethnic group

“Batwa” are the Twa people (with the prefix Ba)

“Mutwa” is a Twa individual (prefix Mu)

The Batwa: A people dispossessed by conservationists and government

The Batwa lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the equatorial forests, gathering edible and medicinal plants, and hunting forest animals. It was a traditional and ancient lifestyle that had existed in harmony with the forest ecosystem for generations.

In the early 1990s, conservation bodies claimed that the Batwa’s very existence threatened the forests and the wildlife, including the endangered mountain gorilla. The Government of Uganda agreed. It coerced, then forced the Batwa from their forest homes; relocating them to farmlands on the edge of the forest.

Unsurprisingly, the Batwa struggled to adapt to alien agriculture practices let alone the sudden forced evacuation from and dispossession of ancestral lands that were so central to their lives, identity, and culture. As a result, they have become one of the poorest and most marginalised groups in Uganda. Mental illness, alcoholism, domestic abuse, and preventable disease are prevalent.

Charity, reorientation, and tourism

The Batwa became a focus of charitable organisations, many of them evangelical in nature, aiming to assist “materially and spiritually”. The Batwa were “educated” to turn their backs on their god (Nyabingi) and their belief systems, which were spiritually interwoven with the forest where they once lived.

They also became the focus of tourism interest. The charitable organisations, along with tourism companies and National Parks authorities, began promoting ‘Batwa Experiences’, an early example of which I witnessed while camping in the Semliki.

For ‘Batwa Experiences’, participating Batwa don non-traditional barkcloth clothes, put on shows, charge for photos, and sell crafts; very little of which is based on their culture.

These ‘Batwa Experiences’ are now offered as part of a visit to forest National Parks. In Mgahinga, for example, a park ranger will tell visitors that they can track mountain gorillas and golden monkeys, climb mountains, walk nature trails, and “see the little people; the forest pygmy”.

‘Batwa Experiences’ feel uncomfortably close to human zoo tourism, with the potential to caricature and even dehumanise a whole community.

Batwa people who try to make a living outside of tourism are also exploited. Racism and bigotry against the Batwa persist throughout other Ugandan communities.

Should we avoid indigenous people?

For indigenous people, the focus and lens of tourists can be unacceptably intrusive.

In 2011, the indigenous Amazonian people of Nazareth village, Colombia, removed themselves from the tourism map. They banned trekkers and tourists and posted guards with bows and arrows to ward off unwanted foreign visitors.

One Nazareth resident reportedly said that some tourists can’t distinguish between wildlife and people; snapping photos of families as if they were animals.

Another said:

“Tourists come and shove a camera in our faces. Imagine if you were sitting in your home and strangers came in and started taking photos of you. You wouldn’t like it.”

With such experiences in mind, it is understandable to question whether it is better for us as tourists and travel professionals to avoid indigenous people altogether; to leave them to themselves; to not include them in anything tourism-related due to all the potential harms.

I believe the real question is not whether we should engage with indigenous people — we should — but how we engage.

A 2017 paper on Indigenous People & Tourism published by Tourism Concern — an organisation that has lamentably ceased to exist — makes this point clearly:

“[Tourism with indigenous people] can be positive: it can assist cultural revitalisation and be a force for empowerment. On the other hand, it may see the often marginalised people and their villages becoming mere showcases for tourists, their culture reduced to souvenirs for sale, their environment to be photographed and left without real engagement.”

How can cultural tourism benefit travellers and those visited?

So how do we as travellers and tourism professionals ensure that our activities contribute to what Tourism Concern calls a “cultural revitalisation” and “empowerment”? How do we establish “real engagement” with indigenous peoples like the Batwa?

Don’t miss other “Good Tourism” content tagged with

“Culture, cultural heritage, & history tourism”

My view is that the tourism opportunity for the Batwa is in moving away from the demeaning fake spectacles and towards their authentic culture; to tourism activities that offer sustainable livelihoods, autonomy, ownership, and involvement in the wider tourism industry.

As tourism professionals and travellers we should support and promote that.

We should, for example, seek out Batwa guides to lead tours through the forests that were their ancestral homes. We should ensure that they are paid full guide fees for doing this. (We are told that not one Mutwa makes a full livelihood from forest guiding).

And we should encourage the elders who guide us to bring along younger generations so that they too might maintain their inherited indigenous wisdom.

We should also encourage the Batwa to break through the barriers of prejudice to become professionally involved in tourism more broadly. (We are told that there is not one Mutwa travel professional in Uganda.)

Working in partnership with Twa communities and individuals can begin to break down these barriers and, in some way, provide real recompense to a community that has suffered from misanthropic conservation and tourism practices.

Partnerships and paths less trodden

Real partnership is based on mutual respect and advantage.

Don’t miss other “GT” content tagged with

“Community-based tourism”

Engaging respectfully with indigenous people offers huge advantages to us as travellers and tourism professionals in terms of opportunities to learn; opportunities that can be just as advantageous to indigenous communities.

As travellers and as travel & tourism industry professionals, we still have much work to do to find the right path — a path less trodden — with indigenous peoples.

What do you think? Share your own thoughts in a comment below. Or write a deeper “GT” Insight. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism, because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

“GT” is where free thought travels.

Featured image (top of post): The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, Uganda, a place where the Batwa once lived. Image courtesy of Nomadic Skies.

About the author

Gavin Anderson is an international development professional who now focuses predominantly on sustainable and inclusive tourism. Mr Anderson runs a small experimental travel company, Nomadic Skies Expeditions, which organises slow treks in collaboration with communities in Armenia, northwest Nepal, and Uganda. Gavin also co-founded and is a partner in The Stonehouses in northwest Scotland.