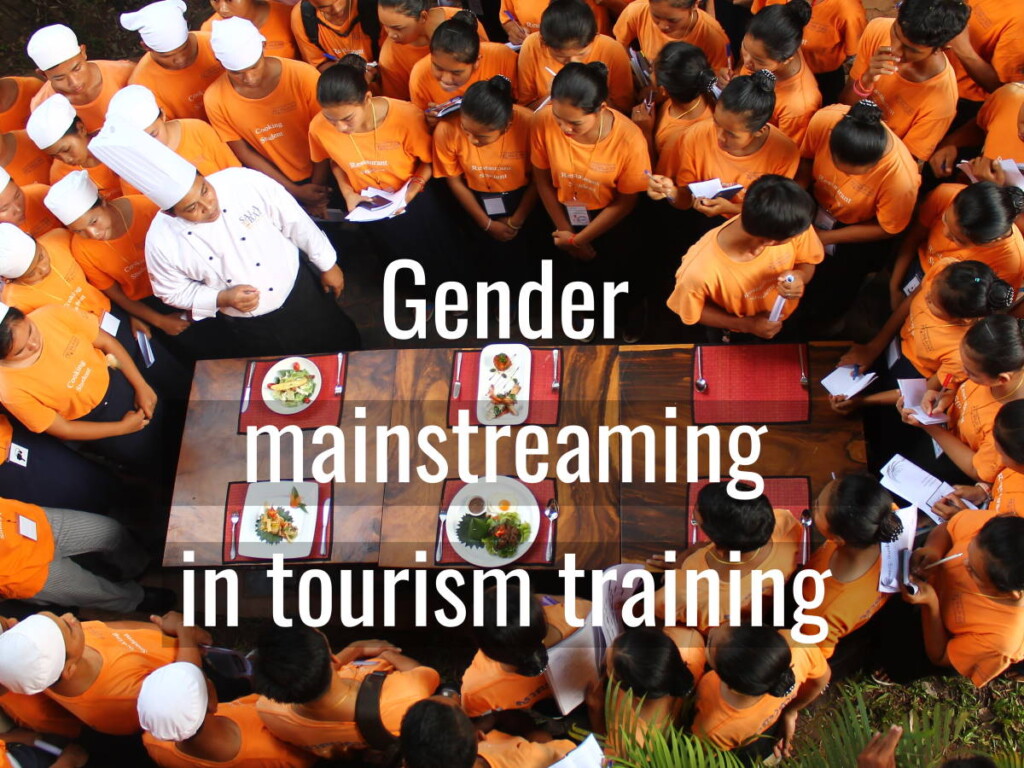

Gender mainstreaming in tourism & hospitality training. What? Why? How?

What is ‘gender mainstreaming’? Why is it important? And how can it be applied in tourism and hospitality training centres?

In the wake of the release of their report on gender mainstreaming, Nguyễn Thị Thu Thảo, Võ Thị Quế Chi, Marlène Vermeij, and Delhi Kalwan of “GT” Partner the Association of Southeast Asian Social Enterprises for Training in Hospitality & Catering (ASSET‑H&C) share this “GT” Insight.

[You too can write a “Good Tourism” Insight.]

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), more than half of those working in tourism and hospitality are women. However, they tend to occupy the lowest-paid jobs.

Ensuring gender inclusiveness in hospitality and catering schools can contribute to a more equal industry — and society.

This is achievable through gender mainstreaming.

What is ‘gender mainstreaming’?

“Mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in any area and at all levels.”

International Labour Organization

Gender mainstreaming is a long-term effort that requires multi-faceted strategies.

Gender mainstreaming in tourism & hospitality training

Several tourism vocational schools in Southeast Asia, within their specific contexts, have implemented both formal and informal mechanisms to respond to students’ needs, including, but not limited to, gender issues.

While women form the majority of the tourism workforce, they are often reduced to certain gender stereotypes, such as waitressing and cleaning in the kitchen.

Parents, therefore, are reluctant to let their daughters work in the industry.

Don’t miss other “Good Tourism” posts tagged with ‘Women’

The economic and tourism slowdown brought by the pandemic further exacerbates this problem. Families would rather have their children work and contribute to the household income than enrol them in a vocational school.

This has resulted in a drastic decrease in student enrollment, especially for girls.

In order to address this gender issue and tackle the potential labour shortage in tourism, building gender inclusive recruitment and safeguarding mechanisms in tourism schools can be the first crucial step.

In our recent publication, Promoting Gender Mainstreaming: Recommendations for vocational training centers, we at the Association of Southeast Asian Social Enterprises for Training in Hospitality & Catering (ASSET‑H&C) suggest how to improve and ensure gender inclusiveness in hospitality and catering vocational training centres.

Don’t miss other “GT” posts tagged with ‘Inclusive tourism’

& ‘Travel & tourism education and training’

We believe this will help pave the way for a more equal industry and society.

Tailored to the needs of ASSET‑H&C’s 12 members across Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, the recommendations are based on applicability and actionability.

Furthermore, ASSET‑H&C anticipates that this publication will inspire other stakeholders in the tourism industry to identify inequalities and take action to create a fair working environment for all.

Examples of gender mainstreaming at tourism & hospitality training schools

Gender audits and gender equality action plans

Approximately 54% of students at ASSET‑H&C member schools are women.

After proper gender audits, and by using participatory methods, schools can use the findings to establish ‘gender equality action plans’.

All member schools have been successful in implementing context-specific strategies to target under-represented groups.

For instance, KOTO (Know One Teach One) and the Australian Government have been working together to improve the lives of young Vietnamese women from remote and disadvantaged ethnic minority communities through a comprehensive three-year project called ‘Her Turn’.

Safety and gender responsiveness

It is also important to create safe classroom environments and to build gender responsiveness in vocational training centres.

Most ASSET‑H&C members have formalised safeguarding regulations. These can be in the form of dedicated safeguarding policies and procedures — child-safe policies, gender equality policies, and employee policies — in regulations and contracts.

At Bayon Bakery and Pastry School, for example, internal regulations on how to prevent abuse and to respect classmates are defined by students under the supervision of the school’s social worker.

Member schools also work with training partners to ensure communication and safeguarding mechanisms are in place.

Some schools integrate safeguarding clauses in their internship contracts.

Schools have also set up monitoring bodies, such as a student affairs committee, to flag cases of abuse to the school’s Director.

Also see the “GT” Insight by Hartman, Nguyễn, and Võ

“How can vocational education contribute to women’s empowerment?”

Life skills training

At most ASSET‑H&C schools, students learn about abuse and their rights during life skills training modules. These classes provide an opportunity to discuss gender equality and sexual and reproductive health. Students also develop the interpersonal skills necessary for their personal and professional growth.

At Sala Baï Hotel and Restaurant School, beauty therapy and housekeeping students join an additional workshop to establish safety protocols. These students are more exposed to abuse than students from other departments.

At Ecole d’Hôtellerie et de Tourisme (EHT) Paul Dubrule, such training happens before students commence their internships.

“At Spoons Cambodia (formerly known as EGBOK), the students, both men and women, undergo comprehensive classes on women’s empowerment and gender equality, going into various social and gender issues such as marriage, love, relationships, child rearing and financial matters.”

Valued, Paid, Recognized: Desk Review of Business Efforts in Promoting Women’s Empowerment in the Mekong Hospitality and Tourism Sector

Similar training sessions are also included in the curricula of Hospitality & Catering Training Center (HCTC) (Thailand), La Boulangerie Française (Vietnam), PSE Institute (Cambodia), and Don Bosco Hotel School (Cambodia).

The internal sharing of these practices can inform next steps, such as in-depth audits.

Furthermore, these commendable efforts, and the others laid out in the report, can serve as powerful examples for external stakeholders.

Engaging external stakeholders

Engaging stakeholders outside the school environment is also important in forwarding the goals of gender mainstreaming.

Students’ families

Families, particularly in rural, low-income, and marginalised communities, have significant influence on their children’s career paths.

During workshops with teachers and staff from three ASSET‑H&C‑member schools in July 2021, many participants stated that when it comes to gender mainstreaming, working with families is one of their biggest challenges.

“I remember one graduation ceremony a few years ago. Everyone was happy and celebrating, but one student was crying. Some of her relatives were working on a cruise, and her family wanted her to do the same upon graduation.

“This student, however, wanted to continue studying at university […] I was able to convince the mother to let her daughter pursue her ambition. The student went back to her hometown and became a trainer in a restaurant operated by a NGO there while attending classes on weekends.”

Sokhy Chea, F&B Trainer, Sala Baï Hotel & Restaurant School

Other tourism & hospitality training schools

Partnerships between vocational training centres are also a great way for them to build capacity in gender mainstreaming, harness local and international expertise on the topic, and demonstrate commitment to their trainees.

For instance, before the pandemic, the six ASSET‑H&C members based in Cambodia established a common policy that employers need to pay interns a minimum allowance of US$40 for a four-week internship.

This type of strategic partnership leverages schools’ negotiation powers, allowing schools to amplify advocacy for their students and graduates.

Conclusion

ASSET‑H&C’s member schools provide the opportunity for disadvantaged students to develop their skills, join the tourism workforce, and contribute to their community.

The network and its members pay particular attention to instilling a progressive mindset in the educators and tourism workers of tomorrow.

Sustainability is a key part of this journey, from protecting the environment to building decent and fair working conditions.

Gender mainstreaming allows inclusion and provides many additional benefits, such as improved retention rates in the tourism & hospitality job market, and consequently, easier student recruitment for vocational schools.

Building awareness and inspiration around issues of gender inclusiveness and sustainability among those in higher management positions to those early in their careers, will contribute to a more equal industry and equitable society for all.

What can you do to promote a more equal industry?

Download the full gender mainstreaming report to learn about all the recommendations and to be inspired.

What do you think? Share a short anecdote or comment below. Or write a “GT” Insight of your own. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion about travel & tourism because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

About the authors

Nguyễn Thị Thu Thảo, Võ Thị Quế Chi, Marlène Vermeij, and Delhi Kalwan co-ordinate the activities of the Association of Southeast Asian Social Enterprises for Training in Hospitality & Catering (ASSET‑H&C). The network promotes exchanges and mutual development for 12 member schools across Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam that provide tourism and hospitality vocational training for vulnerable youth.