You can’t furlough an elephant: How Laos’ ECC is surviving the COVID crisis

What would you do if revenues dried up but you had dozens of elephants to look after? The Elephant Conservation Center (ECC) in Sayaboury, Laos faced this situation as COVID-19 lockdowns and travel bans bit in March 2020. ECC founding partner Sébastien Duffillot shares what they did.

It’s a “Good Tourism” Insight. [Thanks to “GT” Destination Partner We Are Lao for inviting Mr Duffillot to write a “GT” Insight.]

The tourism industry has been particularly badly hit by the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020. For many operators it has meant bankruptcy or at least freezing operations and furloughing staff.

The situation has highlighted the fact that tourism — a non-essential activity — is an industry that is hit both first and hardest in a global crisis. It has exposed the travel & tourism industry’s fragility, relying as it does on the freedom of people to travel.

A tourism sector with which I am very familiar, and which is popular among many visitors to Southeast Asia, is elephant tourism.

In this post I will describe the steps we at the Elephant Conservation Center of Laos (ECC) have taken since the start of the pandemic.

Our experience has been very different to those of most tourism businesses, including hotels, resorts, and restaurants. The main point of difference is that we are currently in charge of 30 elephants.

Live animals under human care cannot be furloughed nor made redundant. And neither can their caretakers.

This means that for an organisation like ours that used to employ 70 staff before the pandemic, we could suspend jobs for only 30 of them. After about a year without visitors, we had the difficult job of asking all personnel associated with the hospitality part of our business — tour guides, drivers, housekeepers — to leave the company.

Our team of 24 mahouts, however, are essential to the elephants. They cannot be let go. We also have to retain veterinary staff to ensure that our herd receives the best care. They all need food and accommodation, meaning that we have to employ kitchen, maintenance, and technical staff to keep the place running.

All told it is with a team of about 40 people and high operational costs that the ECC has been sailing the angry seas of the COVID era until now.

Also see Hollis Burbank-Hammalund’s “GT” Insight

“Tourism in crisis: A Myanmar elephant camp pivots to plan B”

What makes us special?

International travel and tourism may take off again, but it looks like it will be a while before we can get back to pre-COVID levels. It will be a long time, in my opinion, before we can fully recover and generate the kind of income we were used to.

So, in order to avoid bankruptcy, we are analysing what makes us special and what are our strengths and weaknesses.

We now ask ourselves regularly: “How can we survive this crisis?” and “What can make us resilient to this and future dramatic changes in our business environment?”

We realise that besides being a place open to tourists — who pre-COVID contributed a whopping 85% of our turnover — we also have a long history as a conservation and educational organisation.

We have started looking at our facility as the perfect place for researchers, students, and scientists who are keen to study elephants and their ecosystem.

What other place can offer a group of 30 Asian elephants — calves, juveniles, cows, and bulls — to study in their natural habitat?

Our fully equipped endocrinology lab and elephant hospital, 4G internet access, vehicles, rooms, and restaurant can easily accommodate those interested in fieldwork.

Also see Anabel Lopez Perez’ & Hollis Burbank-Hammarlund’s “GT” Insight

“Science, mahout traditions may help save elephants from extinction”

And we can leverage our ongoing partnerships with the Smithsonian Institution; the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD); the Department of Botany, Faculty of Natural Sciences and the Faculties of Pharmacy and Veterinary Medicine, National University of Laos; the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand; International Elephant Project; Elephant Care International; Asian Elephant Support; and the Asian Captive Elephants Standards.

We have turned to these partners to express our need and want to diversify our activity; to cater to the specific needs of their scientists, researchers, faculty, and students and welcome them to our premises.

We know that it will take time to successfully transition to a sustainable model that does not rely so heavily on tourism.

However, adopting this strategy has already brought positive results:

- Our team has developed a common vision and now share common goals in a time of distress. This has brought new hope and energy to what we do.

- Choosing this direction hasn’t meant completely dropping our previous core business of welcoming lay people as tourists. We look forward to offering them an even deeper experience when they return.

- The strategy takes the ECC further along in its founding mission to become a conservation centre for Asian elephants. Working alongside scientists and conservationists as a core activity (rather than an occasional one) will doubtless raise our scientific standards and credibility.

Education has been integral to our work since founding.

Through our many educational activities and publications, including mobile libraries, our Kids in Conservation initiative, and “The elephant: an Asian Symbol” exhibition, we have built capacity within our team to teach in Laos and abroad.

That’s why we are investing more this area.

For example we have produced a touring exhibition in France that generates an income for the ECC. We are also developing an educational kit for the French public education system. Closer to home, we are devoloping an elephant museum in the World Heritage town of Luang Prabang.

All of these projects can and do bring in revenue for our conservation work.

Doubt and depression is not an option

To conclude, once we finally understood that a return to pre-pandemic conditions was unlikely in the near future, redesigning the ECC model became a pressing necessity.

It is absolutely vital that we diversify our activities based on our strengths and ongoing partnerships. To ensure a bright future for all our stakeholders, we need to establish a firm base and build on it through our experience and expertise.

To rethink one’s activity and business model is not an easy task. But to give up to doubt and depression is not an option when one is in charge of endangered animals.

Also see John Roberts’ “GT” Insight

“Tourism elephants lose when pragmatism gives way to politics, ideology”

Science and education have become the centre of our vision for the future. We know that tourism, supplemented with crisis philanthropy, is unsustainable in the long run.

For us, diversification is the way we feel we should go. And so far it has brought with it a shining light of hope for our pachyderms, people, and partners.

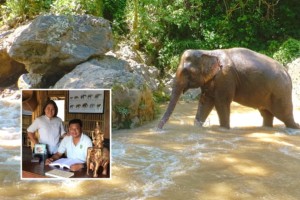

Featured image (top of post): One can’t simply furlough a bull elephant and his mahout. Image supplied by the Elephant Conservation Center in Sayaboury, Laos.

About the author

Sébastien Duffillot is a founding partner of the Elephant Conservation Center in Sayaboury, Laos as well as co-founder of the NGO ElefantAsia. An active member of the IUCN Asian Elephant Specialist Group (IUCN SSP AsESG) and the Asian Captive Elephant Working Group (ACEWG), Mr Duffillot also serves as president of the NGO Des Elephants et Des Hommes. Sébastien is author of The Elephant Caravan (Actes Sud, 2003) and Walking with Giants (Actes Sud, 2016).