Seven ‘deeper leverage points’ for travel & tourism’s effective climate action

Academics Johanna Loehr and Susanne Becken offer an executive summary of “Leverage points to address climate change risk in destinations”; their paper recently published by Tourism Geographies.

It’s a “Good Tourism” Insight. [You too can write a “GT” Insight.]

The latest science is clear. Climate action needs to step up drastically.

This also affects tourism. As we have seen at the Glasgow COP26, the tourism sector is beginning to grapple with climate change as a significant factor in its future.

Also see Ken Scott’s “GT” Insight

“Why travel & tourism is wrong to embrace net zero”

However, whilst the need for change is sinking in, the magnitude of the change is not.

This is not uncommon. Humans always tend to address small things instead of tackling the more fundamental ones.

Some might call this window-dressing. For others it is everyday psychology. We go for low-hanging fruit first, incremental change or nudging, rather than completely redesigning the system (or ourselves).

Also see Tanner C Knorr’s “GT” Insight

“Climate change, COVID-19, and the need for global systemic change”

This has long been recognised in the concept of ‘leverage points’ developed by Donella Meadows 20 years ago.

The concept of levers explores what types of changes are ‘shallow’ (easier to implement but not so effective) and what changes are ‘deeper’ (much harder to do but more effective in addressing the problem or challenge).

We know a lot of the easy ones for tourism and climate change, such as changing light bulbs, reusing towels, or perhaps driving a smaller car.

We know less about the more tricky ones.

Also see Daniel Rye’s “GT” Insight

“It’s mental: Why remote resorts are resisting renewable energy”

Looking at the tourism system then, what types of changes or pathways do we need to consider to work our way from the shallower to the deeper leverage points?

In our paper we use Vanuatu as a case study to look at the ‘tourism system’ and the climate action that is either already happening there now or could happen in future by building on existing efforts or trends.

Vanuatu experienced fast-growing tourism before COVID-19, especially from cruise ships. While the foreign exchange earnings were welcome, growing arrival numbers had started to cause problems, especially in the smaller islands that were not prepared for an influx of visitors and everything they bring.

Also see the “GT” Insight by Movono, Scheyvens, and Auckram

“What do the people want? Reimagining Pacific Island tourism”

These problems are being recognised now in new tourism strategies that reflect an approach that balances tourism growth, community prosperity, and its effects, including its effects on the climate.

These new tourism sector strategies already employ leverage points that are deeper than what was seen previously.

For addressing climate concerns, especially deep levers need to be employed.

The seven leverage points identified in our study are:

1. Climate engagement

One of the first leverage points is climate engagement.

The tourism sector needs to actually engage with climate change at the policy level.

This means understanding what the government’s policy on mitigation and adaptation is and how tourism can contribute.

In some cases this might mean examining how tourism must change so as to avoid undermining climate goals.

Better coordination between tourism departments and environment and climate ministries is essential.

2. Climate finance

Deeper engagement leads into the second leverage point of climate finance.

Often, investment into decarbonisation or climate adaptation does not specifically focus on tourism’s needs.

Indeed tourism can miss out altogether as, without new investment, the sector can’t contribute to climate action and can become even more of a burden.

Maladaptation is when climate-related action makes reducing emissions across the tourism sector more difficult. An example is investing in air conditioning for the comfort of visitors without also investing in an appropriate source of energy for that luxury.

Investing in electric boats for visitor transportation is an example that is appropriately aligned to tourism’s needs, climate adaptation, and decarbonisation imperatives.

3. Working with nature

Working with nature rather than against it is a third leverage point that seems to make sense, but is often not implemented.

Replanting forests (or wetlands) to stabilise shorelines, create important habitat, and sequester carbon is a prime example.

4. Dedicated research

Working with nature highlights a need for more dedicated research to generate data that will allow us to track tourism’s climate action, monitor its effects, and better innovate responses.

5. Local participation

Another lever for deeper climate action is local participation.

Readers of The “Good Tourism” Blog would know about the importance of understanding community needs as well as local ecosystems.

The empowerment of locals is key. This might be difficult for those who are currently ‘in charge’ of the tourism system, as it means sharing power and distributing governance differently.

It might also not be easy to find the best mechanism for ‘citizen/community’ participation and decision making, for example a ‘resident assembly’ or referenda.

Whatever the mechanism is, it needs to come with adequate resourcing!

6. Redefine tourism’s goal, and 7. Shift the paradigm

Finally, the two hardest, or deeper levers are to redefine the goal of tourism and, with that, shift the paradigm of what we believe matters.

For example, what do we mean by wealth and well-being?

Do we feel that ‘equity’ is a core value? (And what does ‘equity’ mean, anyway, in different cultural contexts?)

Do we see ourselves as part of nature or in control of managing it?

There are other questions like that to answer.

Some countries, including Vanuatu, are questioning tourism’s previous goal of maximising economic output.

Instead, community well-being is playing a more central role similar to the Living Standards Framework used in New Zealand or Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness.

Again, approaches need to be appropriate for the culture and place. It is likely that a global ‘cookie cutter’ solution will not work.

However, what is clear is that any change of answer to the question of “What is tourism for?” will have a profound impact on how we evaluate success, how we invest resources, and how we prioritise or resolve trade-offs.

Tourism is currently on a journey towards employing ever deeper leverage points.

For those who want to participate in the ‘tourism of the future’, it might be worthwhile thinking about where they sit on the spectrum of transformation, and for how long they can afford to continue operating with yesterday’s goals and values.

This “GT” Insight is based on a paper by the authors entitled “Leverage points to address climate change risk in destinations” that was published online on November 30, 2021 by the journal Tourism Geographies.

Agree? Disagree? What do you think? Share a short anecdote or comment below. Or write a “GT” Insight of your own. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion about travel & tourism because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

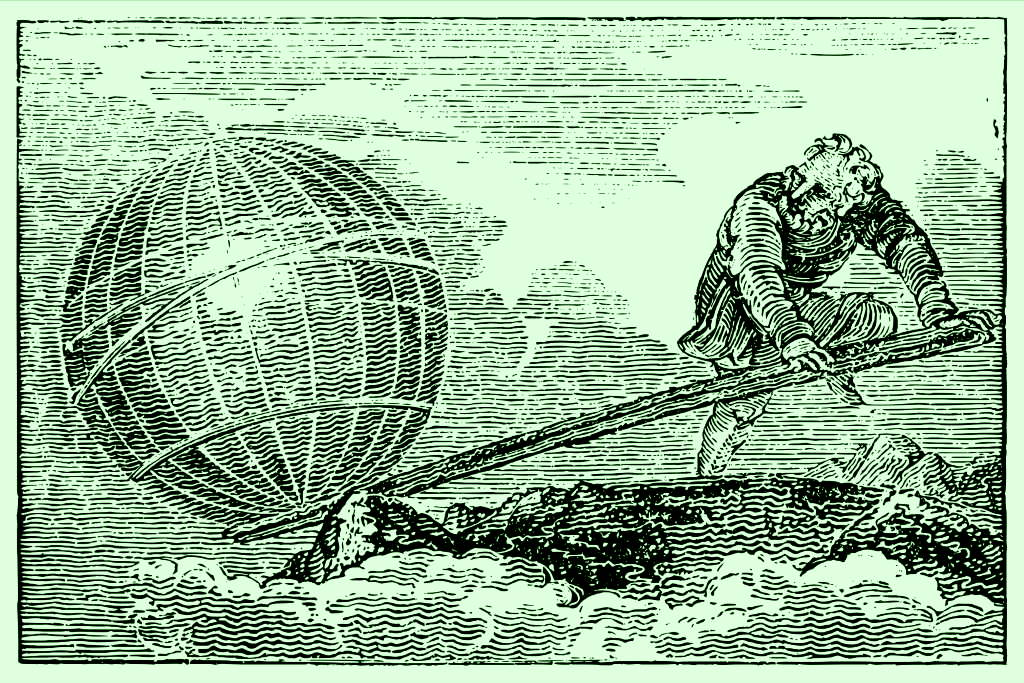

Featured image (top of post): “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.” _ Archimedes

About the authors

Johanna Loehr is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Griffith Institute for Tourism (GIFT) in Australia. Dr Loehr completed her PhD at Griffith University in 2020.

Johanna wants to help tourism address climate change. “My work focuses on how tourism can increase net benefits and values to the wider destination, including host-communities and the local environment. My research interests include systems thinking, tourism and climate change, sustainable tourism, well-being, and policy.”

Susanne Becken is a Professor of Sustainable Tourism at Griffith University, and was the founding Director of GIFT. Dr Becken is also the Principal Science Investment Advisor (Visitor) for the Department of Conservation, New Zealand and is the Vice Chancellor Research Fellow at the University of Surrey in the UK .

Susanne is a member of the Air New Zealand Sustainability Advisory Panel, and sits on the Advisory Boards of My Green Butler, NOW Transforming Travel, and the Whitsunday Climate Change Innovation Hub. A Fellow of the International Academy of the Study of Tourism and the 2019 UNWTO Ulysses Award winner, she has published more than 100 articles on sustainable tourism, climate change, and tourism resource use.