‘Jouissance’: The pleasure & pain of ‘ethical donor tourism’ in Africa

Some of the very wealthy among us love to live large in Africa’s magnificent landscape, to observe (and hunt) its iconic wildlife. While they are there it is good that they give generously to economic development, philanthropic, and conservation projects, no? Are we missing something? Academics Stasja Koot and Robert Fletcher think so.

It’s a “Good Tourism” Insight. [You too can write a “GT” Insight.]

In this “GT” Insight we will explore two novel types of ‘ethical donor tourism’, based on two recent academic papers about ‘philanthrotourism’ and ‘environmentourism’.

Both are often presented as supporting social and environmental causes.

However, this positive self-presentation may obscure how they actually benefit from and reinforce inequalities and environmental degradation.

For travel & tourism practitioners it is important to be aware of what motivates donors to engage in tourism practices, what such tourism conceals, and to include this knowledge in decision-making involving ethical donor tourism.

After introducing philanthrotourism and environmentourism, we provide a brief critical analysis drawing upon the psychoanalytical concept of jouissance.

Jouissance is a particular type of ambivalent enjoyment that goes beyond ‘pure’ pleasure. It also encompasses an element of discomfort, or even pain, when confronting distasteful aspects of social or environmental problems.

In both philanthrotourism and environmentourism such problems and the jouissance they stimulate are at the core of the tourist experience.

We further relate jouissance to philanthrocapitalism in which global elites claim to revolutionise philanthropy by applying the business savvy that made them successful.

Often, however, this means a concentration of power in the hands of elites and a neglect of more structural social and historical elements.

Philanthrotourism: Eliding structural and historical causes of inequality

Philanthrotourism refers to the growing phenomenon in which NGOs offer trips to ‘major donors’ to visit development or conservation projects. Such excursions have become ever more common and constitute a relatively new tourism niche.

Thus far, most studies of ‘ethical tourism’ focus on the widespread use of tourism as a strategy to generate foreign exchange, local development, and nature conservation.

For instance, in a specific form of ‘development tourism’ excursions are organised by (Western) NGOs to their development projects. They inspire participants to become more socially and environmentally aware.

In ‘travel philanthropy’, the focus is on people wanting to ‘do good’ during their travels. Its starting point is the growth of ‘volunteer tourism’.

While philanthrotourism overlaps with these other forms of tourism to some degree, it also exhibits significant differences.

Also see Tanner C Knorr’s “GT” Insight

“Running water: Tourism take a second look in Tanzania”

In development tourism, for instance, the leisure practice of tourism and the professional practice of development are clearly separated between the development agents and the tourists. Moreover, there is no clear focus on big donors.

By contrast, philanthrotourism is focused on major donors, especially the corporate sector. The intention is to build long-term relationships with fundraising in mind.

Philanthrotourism also differs from travel philanthropy and volunteer tourism in that the latter two are considered phenomena originating from the tourism industry, whereas philanthrotourism originates from civil society.

In philanthrotourism, moreover, participants do not normally ‘work’ (voluntarily or involuntarily) during the trip, as do the (often young) volunteer tourists.

In philanthrotourism, major donors join a trip with a small and select group of other (actual or potential) donors, mainly to witness the projects they support.

Also see Lieve Claessen’s “GT” Insight

“How a small South African backpackers is making a big difference”

An example of an NGO that organises donor trips is the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF), which offers full travel packages to donors through WWF Travel.

Likewise, Conservation International (CI) offers private luxury trips to their conservation sites. Packages arranged through their in-house luxury travel firm include yacht rentals, cruises, and other products to please potential philanthropists.

Development NGOs such as We Charity and Plan International, among many others, have also organised tours for major donors.

Today, some commercial travel operators offer to fully organise such trips for NGOs. Philanthropy Without Borders, for example, states that “[b]y offering your donors a transformative experience in the field they will be ready to deepen their commitment”. Elevate Destinations offers “to win your donors’ hearts through travel”.

Philanthrotourism visits to development and conservation projects are constructed in such a way that donors receive a carefully orchestrated guided tour.

Also see Adenike Adebayo’s “GT” Insight

“Delicious, nutritious, precious: Nigeria’s ‘Slow Food’ tourism potential”

The first author (Stasja Koot) used to work as a major donor fundraiser at an NGO. In this capacity he co-organised two donor trips, to Kenya and Ethiopia, where local allies would advise how to frame the NGO’s projects as successful, or of great potential.

The local allies would explain the projects to guests during quick site visits without paying any attention to the structural and historical causes of the poverty and inequality encountered on the trips.

This left the elite guests (in this case a combination of NGO representatives and major donors) largely unaccountable for their role in the overarching structural social and environmental issues.

Some donors were impressed with a project in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where orphans were allowed into the school but had to spend the night on the streets. This made the donors aware of the relatively luxurious life of the foreign travellers.

Environmentourism: Conserving consumerism and the land it requires

The dominant narrative around tourism in Africa is that tourists are considered privileged, mostly Western and white, who come to gaze upon African people (who are considered ‘less developed’) but mostly to observe Africa’s wildlife.

In a different part of Africa, namely at the private nature reserves to the west of Kruger National Park, South Africa, a high-end tourism industry thrives.

The industry here is ‘excessive’ in the sense that it promotes elitist lifestyles based around exorbitant material consumption.

This suggested to us a new term: ‘excessive environmentourism’.

The term ‘environmentourism’ is inspired by ‘developmentourism’: Because the development [environmental] impact of tourism itself is important, “the merging of development [environment] and tourism” into a single practice means that it should be referred to by a single word.

Also see Shamiso Nyajeka’s “GT” Insight

“Zambia’s tourism potential & its prospects for a green economy”

In environmentourism, the strong focus on excessive consumption is presented as an ultimate experience of pleasure and relaxation while at the same time ‘doing good’ (as in philanthrotourism, wealthy tourists are approached for donations too).

Unlike in ecotourism, environmentourism excludes ‘local communities’ from the benefits of tourism activity. Environmentourism only focusses on addressing environmental concerns, completely ignoring local communities’ well-being.

Environmentourism, like philanthrotourism, overlaps with other types of ethical tourism, such as volunteer tourism. However, when compared to volunteer tourism, environmentourism has a stronger focus on a nature-based experience.

Like some nature-based volunteer tourism, environmentourism also “creates value in the trade of experiences in or with ‘nature’”, however volunteer tourism is much more youth- and budget-focussed.

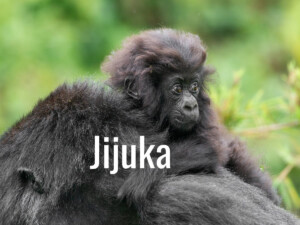

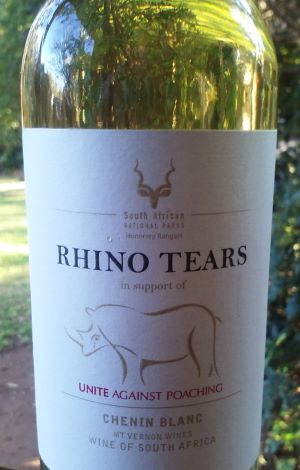

On the South African private reserves, many tourists learn about the rhino poaching crisis, and want to contribute to fighting this.

There are now many philanthropic tourist initiatives to ‘save’ the species by providing financial and in-kind support.

Consequently, high-end tourist lodges have now developed a rather large and intriguing suite of activities through which tourists can join this fight.

They can, for example, take part in activities to microchip rhinos (and their horns); visit and donate to a rhino orphanage; tour an anti-poaching unit; or visit the world-famous all-female unarmed anti-poaching unit the Black Mambas.

One activity that stands out is the opportunity to join in the translocation of rhinos to ‘safer’ havens (where anti-poaching policies are much stricter): “Eight adrenaline-fueled days rescuing rhinos in South Africa and Botswana”; a tour that was heavily promoted by actress Uma Thurman.

Drenched in luxury, the trip is expensive: US$18,655 per person and a tax-deductible requirement of US$25,000 per person for the Wilderness Wildlife Trust to Rhino Conservation Botswana.

Many luxury operators, lodge owners, and managers would emphasise the importance of tourism in Africa for the survival of wildlife.

Absent from this discourse are the often deplorable labour circumstances at the private nature reserves, failing public services, racial and socioeconomic inequalities, and land ownership injustices that were created under colonialism and apartheid.

In this way, environmentourism legitimises the existence of high-end privatised tourism; both its excessive consumerism and the land it requires.

Also see James Nadiope’s “GT” Insight

“How bees, trees, & tourism reduce human-wildlife conflict in Uganda”

The example of rhino translocations does not stand on its own.

At other luxury tourism companies in in Tanzania, tourists are invited on “safaris with a purpose” to fit elephants with GPS collars: Four nights/five days full board safari, including game drives, all meals and beverages, archery, wine tastings, and tennis from “USD 19,464 for 4 people plus a tax deductible contribution of USD 25,000 per person”. More examples can easily be found.

Collaborations with communities, however, should, according to a tourism CEO, be done with community development committees that are “as apolitical as possible”.

This confirms the tendency to neglect structural causes of conservation problems, disregarding problematic aspects of neo-colonial, racial, and ethnic power inequalities within the South African tourism industry.

‘Jouissance’: The pleasure of ethical tourism. The pain at its heart.

In both papers, we found that philanthrotourism and environmentourism are important ways for donors to experience jouissance as a core driver of ethical donor tourism.

Jouissance is a particular type of ambivalent enjoyment that goes beyond ‘pure’ pleasure to encompass an element of discomfort or even pain in confronting distasteful aspects of social and environmental landscapes.

In our case these included orphaned children, poverty, poached rhinos and the idea that these animals will soon go extinct.

Important for practitioners is to be aware that jouissance functions as a core motivator for donors and tourists to engage with development and environmental problems.

More than an affect or emotion, jouissance addresses the unconscious and irrational; it is structured by specific fantasies that inform our sense of reality.

Also see Nirmal Shah’s “GT” Insight

“Overtourism to no tourism in Seychelles: What now for conservation?”

In ethical donor tourism, such fantasies are predominantly based on colonial ideas of the ‘white saviour’ in Africa.

Jouissance is important also in ‘philanthrocapitalism’.

In philanthrocapitalism, both civil society organisations and private sector firms assert that reorganising aid according to neoliberal market principles holds the key to reforming development and conservation moving forward.

Previous forms of philanthropy are generally regarded as largely ineffective because they lack grounding in sound business principles.

Philanthrocapitalism’s effectiveness has thus far not been proven, and it has been critiqued for concentrating wealth and power among the rich and thus lacking democratic decision-making.

Moreover, it is seen to instil principles of competition within civil society while ignoring the broader structural issues at the heart of the inequality and environmental problems it intends to address.

This translates into a lack of accountability for philanthrocapitalists.

Also see Edwin Magio’s “GT” Insight

“Africa must put communities, conservation at the centre of recovery”

Engaging with philanthropy through philanthrotourism or environmentourism generally strengthens donors’ positions as global social and economic elites, creating a situation in which inequality itself is a starting point for jouissance.

As novel types of ‘ethical donor tourism’, both ‘philanthrotourism’ and ‘environmentourism’ illustrate the expansion of philanthrocapitalism, and are subject to critique on similar grounds.

These critiques include their concentration of economic and decision-making power into the hands of a privileged elite.

This is important for travel & tourism practitioners to keep in mind if they feel like joining these trends. Awareness of this can make one pay more attention to the structural causes of this type of tourism, and of ethical tourism more generally.

Featured image (top of post): Zebra stripes at Dikhololo Game Reserve, Brits, South Africa. Photo by David Clarke (CC0) via Unsplash.

Authors’ recommended reading

- Baptista, João Afonso. 2017. The good holiday: Development, tourism and the politics of benevolence in Mozambique. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Brondo, Keri Vacanti. 2015. “The spectacle of saving: Conservation voluntourism and the new neoliberal economy on Utila, Honduras” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 23 (10):1405 – 25.

- Holmes, George. 2011. “Conservation’s friends in high places: Neoliberalism, networks, and the transnational conservation elite” Global Environmental Politics 11 (4):1 – 21.

- Koot, Stasja. 2021. “Enjoying extinction: Philanthrocapitalism, jouissance, and ‘excessive environmentourism’ in the South African rhino poaching crisis” Journal of Political Ecology 28 (1).

- Koot, Stasja, and Robert Fletcher. 2021. “Donors on tour: Philanthrotourism in Africa” Annals of Tourism Research 89.

- Pailey, Robtel. 2020. “De-centring the ‘white gaze’ of development” Development and Change 51 (3):729 – 45

- Wilson, Japhy. 2014. “Fantasy machine: philanthrocapitalism as an ideological formation” Third World Quarterly 35 (7): 1144 – 61.

About the authors

Stasja Koot has been working with indigenous groups in southern Africa, predominantly Namibia and South Africa, since the late 1990s, as a researcher of and a practitioner in community-based tourism. His focus is political and ecological; investigating the power dynamics behind tourism, development, and nature conservation.

Dr Koot is Assistant Professor at the Sociology of Development and Change group at Wageningen University, the Netherlands, and a senior research fellow with the Department of Geography, Environmental Management & Energy Studies, University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Robert Fletcher is Associate Professor in the Sociology of Development and Change group at Wageningen University. Dr Fletcher is the author of Romancing the Wild: Cultural Dimensions of Ecotourism (Duke University, 2014) and co-editor of Nature™ Inc.: Environmental Conservation in the Neoliberal Age (University of Arizona, 2014).