Science, mahout traditions may help save Asian elephants from extinction in Laos

Asian elephants are at risk of extinction in the wild and in captivity. That they are not replacing their numbers in captivity may come as a surprise to many. This is why conservation-oriented captive breeding programs are important to the species. Wildlife biologist Anabel Lopez Perez of Laos’ Elephant Conservation Center and Hollis Burbank-Hammarlund of Work for Wild Life International combine to explain.

It’s a “Good Tourism” Insight facilitated by “GT” Insight Partner Work for Wild Life. [You too can write a “GT” Insight.]

All across the globe, wildlife populations face the very real prospect of extinction. And so it is for Asian elephants.

Once numbering in the hundreds of thousands, rampant deforestation, agricultural expansion, human-elephant conflict, and poaching have conspired to dramatically shrink Asian elephant populations.

Current estimates suggest a mere 30,000 to 50,000 individuals are left, with nearly one-third living in captivity. Without increased conservation efforts, Asian elephants will likely become extinct within 150 years.

Captive elephants can help save wild elephants

In Laos, historically known as the “Land of a Million Elephants”, only about 400 wild elephants currently live in small, fragmented herds in the forests.

An equal number live in captivity and it is this captive population that holds the key to preventing the extinction of the country’s cherished cultural icon.

Located in Sayaboury province, the Elephant Conservation Center (ECC) was established in 2011. Since then, our biologists, conservationists, elephant health care professionals, and mahouts have remained dedicated to establishing a viable captive elephant breeding program. Our program’s mission is to conserve the species, not to breed more Asian elephants into captivity for tourism.

Our key objective is to reverse the low birthrate among the captive elephant population by blending new science and old traditions with a focus on:

- endocrine (hormonal) evaluation to facilitate conception, and

- mahout mastery to ensure the health and welfare of elephant mothers and their unborn and born babies.

From a conservation perspective, Laos’ captive population is a critical genetic reservoir for future elephant reintroduction programs. Therefore, captive elephant reproduction for conservation purposes in Laos is essential to saving the species from extinction.

But just like wild elephant populations in Laos, captive elephant numbers are declining.

Also see John Roberts’ “GT” Insight from June 2021

“Tourism elephants lose when pragmatism gives way to politics”&

Hollis Burbank-Hammarlund’s news article from May 2020

“Health experts seek emergency funds for unemployed elephants”&

David Gillbanks’ news article from March 2019

“Elephants are smart. What if tourism jobs were good for them?”

Female elephants face challenges, including a lack of breeding opportunities coupled with ageing beyond prime reproductive years. Older females often experience physiological problems, such as uterine fibroids and ovarian cysts that prevent conception. Moreover, the window of opportunity for conception is narrow because female elephants cycle only one to four days every four months. And both males and females often exhibit a lack of sexual interest.

The success or failure of today’s breeding programs depends, in part, on using available technology to assess reproductive activity. Routine endocrine monitoring is now viewed as an essential tool for making informed decisions about the reproductive management of captive elephants.

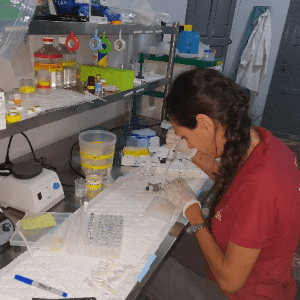

Thanks to support provided by Australian Aid, the Smithsonian, and private donors (including key donors Susan Fulton and Lynette Preston), the ECC was able to establish a fully-equipped endocrinology laboratory in 2019.

The equipment and training our staff received enabled us to accurately monitor our female elephants’ estrous cycles, which in turn has allowed the pairing of females with males at just the right time to maximise the chances of breeding.

Breeding is never forced at the ECC. It’s all done through proper introductions and close monitoring of behaviour. If it happens, it happens. It’s all up to the elephants!

Our new lab also allows us to detect pregnancy at an early stage and to monitor both pregnancy and parturition (the birthing process), making breeding much more efficient, safe, and successful.

Through our efforts, we welcomed two calves in less than one year!

The gift of hope: Baby elephants are born in the forest!

At writing, the newest member of our herd was born on October 4, 2021.

Her mother, Mae Khoun Noi, arrived at the ECC a few years ago when the Government confiscated her along with 11 other elephants as part of an illegal trade bust.

Prior to her arrival at the ECC, Mae Khoun Noi had birthed two calves, neither of which survived delivery for unknown reasons. Once at the ECC, Mae Khoun Noi was included in our breeding program.

Every week, the ECC staff collect blood samples from all the breeding females in order to monitor the estrous cycle of each female. Mae Khoun Noi’s results indicated she was not cycling and thus was not a good candidate for our breeding program. Since she had successfully conceived twice before, however, our staff decided that even if she was not cycling at the time, it was worthwhile continuing to monitor her cycles in case she started to ovulate again.

Persistence (and science) paid off. One year later, Mae Khoun Noi had her first ovulation and was immediately placed with a breeding bull. Soon after, blood checks revealed something truly astonishing. Mae Khoun Noi was pregnant!

Her mahout kept a watchful eye on her health and welfare during the entire pregnancy to ensure Mae Khoun Noi had all the forest and freedom she needed during the entire gestation, enhancing the chances that this pregnancy, unlike her previous two, would result in the birth of a healthy baby.

Upon the calf’s birth, a team of five mahouts took turns monitoring Mae Khoun Noi and her baby 24/7 — ensuring the newborn was drinking milk, sleeping, urinating, and defecating normally. In excellent health thanks to the mahouts’ good care, both mother and baby today share joy in the dense forests of Sayaboury, followed closely, of course, by their astute mahouts.

Mae Khoun Noi’s baby is a blessing. For all of the ECC staff it is a clear confirmation that their combination of science and mahout knowledge will be key to any conservation approach that involves elephants living under human care.

We are extremely proud of ECC’s mahout teams and the important work they do. None of our conservation and welfare efforts (socialisation, release, breeding, veterinary care, etc.) would be possible without them.

Also see Anabel Lopez Perez’ first post

“Mahouts matter: The Elephant Conservation Center’s essential workers”

Faced with the uncertainty of the COVID-19 global pandemic, however, we worry that insufficient funding will jeopardise our conservation efforts.

Please consider a GoFundMe donation to the Elephant Conservation Center. Thank you for caring!

The ECC team sincerely thanks the Elephant Healthcare & Welfare Emergency Lifeline Fund team for its generous financial support. They are helping us pay a fair salary to mahouts, ensuring that all our elephants will have the best welfare and living conditions during these difficult times.

What do you think? Share a short anecdote or comment below. Or write a deeper “GT” Insight. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

Featured image (top of post): Elephant family crossing a river. Captive breeding technology and mahout knowledge may help save Asian elephants in Laos. Image supplied by Anabel Lopez Perez.

About the authors

Anabel Lopez Perez is a wildlife biologist at the Elephant Conservation Center in Laos.

Hollis Burbank-Hammarlund is Founder & Director of “GT” Insight Partner Work for Wild Life International.