WWOOF! An alternative tourism in times of turmoil

Not to be confused with dogging, WWOOFing is a rural tourism concept that combines voluntourism with organic farming and cultural exchange. In this “Good Tourism” Insight, former WWOOFer and current academic Yana Wengel explains why WWOOF and other alternative forms of tourism could be just what we need.

[Thanks to Joseph M Cheer for inviting Dr Wengel to write a “GT” Insight.]

In 2020, the tourism industry was hit by a sequence of emergencies, starting with bushfires in Australia, an aircraft crash in Iran, and then the novel coronavirus that impacted China first and then the rest of the world.

As the COVID-19 virus spread, many major international events, such the Tokyo Olympics, were postponed. Zoom became a household name. And travel & tourism suffered greatly. The industry’s big event, ITB Berlin, was an early casualty. And tourist high seasons all over the world simply didn’t happen. Even Mt Everest was not spared; its climbing season was cancelled outright.

Due to the drastic decline of tourism numbers in most parts of the world in 2020, governments and industry stakeholders scrambled to keep their destinations in travellers’ plans. For example, China’s Hainan Island, “the Hawaii of the orient”, is now offering tourists a free travel insurance product. Other destinations, such as Estonia, have launched favourable visa programs for digital nomads.

UNWTO estimates that a return to 2019 levels (in terms of international arrivals) could take between 36 months and four years.

As a tourism academic, I think we need to spread a positive message about how tourism can still happen, with precautions, as millions of livelihoods depend on it. Hence, in times of turmoil, alternative forms of tourism might be a good plan B.

Alt-tourism

So, what is alternative tourism? Researchers agree that alternative tourism represents an alternative to institutionalised, mass, packaged holidays. Alternative tourism has different forms. It ranges in activity and scope.

Also see Phoebe Everignham’s “GT” Insight

“Tourism’s ‘critical’ rethink and its imperative shift to circular economics”

Alternative forms of tourism are products or services that differ from mass tourism products in terms of supply, organisation, and the involvement of people; hence alternative tourism products often offer a qualitatively different experience, such as a mountain trek or a spiritual pilgrimage.

As an outcome of the global pandemic, some experts foresee a growing demand for some forms of alternative tourism, such as outdoor and nature-based tourism activities, with domestic tourism and ‘slow travel’ experiences attracting more interest.

WWOOFing: What is it?

One such form of tourism is WWOOF which stands for World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms. WWOOF connects people interested in participating in sustainable lifestyles with those who manage organic farms. Farm hosts offer guests an opportunity to engage in local culture and lifestyle. Tourists, who voluntarily work on the farms, receive free food and accommodation in exchange for their labour.

WWOOFing emerged in the UK in the 1970s and has since gone global.

According to WWOOF founder Sue Coppard, the primary aim of WWOOFing is cultural exchange, knowledge development, and learning while working on a farm for four-to-six hours per day. Early adherents of WWOOF believe that WWOOFing offers a win-win exchange: WWOOFers nourish themselves by spending active time outdoors and eating good food while helping farmers sustain organic practices, thus helping the planet. Arguably, WWOOF programmes’ underlying distinctive values and philosophies shape this ‘slow tourism’ experience, which is anchored in the interaction between hosts and guests.

Also see Lieve Claessen’s “GT” Insight

“How a small backpackers is making a big community-based difference”

As a PhD student, I spent nearly 10 months between 2013 and 2014 researching and working on organic farms in New Zealand, UK, and Nepal. My research aimed to go beyond the commercial side of tourism and explore why people engage in this not-for-profit volunteer exchange.

My findings showed that these experiences are shaped by participants’ desire to connect with each other and share meaningful experiences. While participating in an exchange programme, farmers and volunteers share cultural and educational experiences based on trust and non-monetary exchanges that help build a sustainable global community.

The central element of the WWOOFing experience is about people who share work, food, social time, and rules. The interactions between WWOOFing participants are deep, meaningful, and diverse. WWOOFing participants contribute to the organic movement and sustainable food production as well as promote cultural and educational experiences that align with Sustainable Development Goals. Previous studies suggest that WWOOFing is more meaningful compared to mainstream forms of tourism.

WWOOFing: What’s in it for travellers?

Travel. Considering the global pandemic, WWOOFing is an opportunity to travel domestically at little cost, reconnect with the land and nature, and participate in various activities like gardening, taking care of animals, and even ecological restoration projects.

Some WWOOF hosts even welcome families with children.

Many volunteers claim that WWOOF is a transformational experience in which they acquire new skills, learn languages, and gain knowledge of cultures and regions. And they get to connect to a place; live like a local for a while.

WWOOFing: What’s in it for farmers?

Labour. Work gets done and done faster. Not only that, farmers have a chance to meet new people. And they get to travel too. Vicariously, at least.

During my research, farmers told me that because they are tied to the land they lack the opportunity to travel. Still, the WWOOFing experience provides them the opportunity to ‘travel through the volunteers’ stories’. They draw from the energy of young WWOOFers.

Farmers related the learning opportunities they receive as part of their WWOOFing experience. With helping hands on the land, WWOOFing gives them the space for personal growth and the time to master new skills such as time management and interpersonal communication. One farmer, Rachel, a former WWOOF guest and now an experienced host, mentioned that her self-confidence and self-esteem grew from WWOOFing as her communication skills improved.

Also see Aadyaa Pandey’s “GT” Insight

“How a community-based homestay network empowers women in Nepal”

Tourism scholars and industry stakeholders have traditionally paid little attention to alternative travel programmes, non-monetary tourism exchange initiatives, and non-commercial hospitality schemes. But maybe it is time to stop thinking that hosts and guests interact only on the level of economic exchange? Perhaps, since we have been living in a time of turmoil for more than a year, it is time to travel slow, travel local, and reconnect more meaningfully with people and place?

We can start in our own backyards.

What do you think? Share a short anecdote or comment below. Or write a deeper “GT” Insight. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

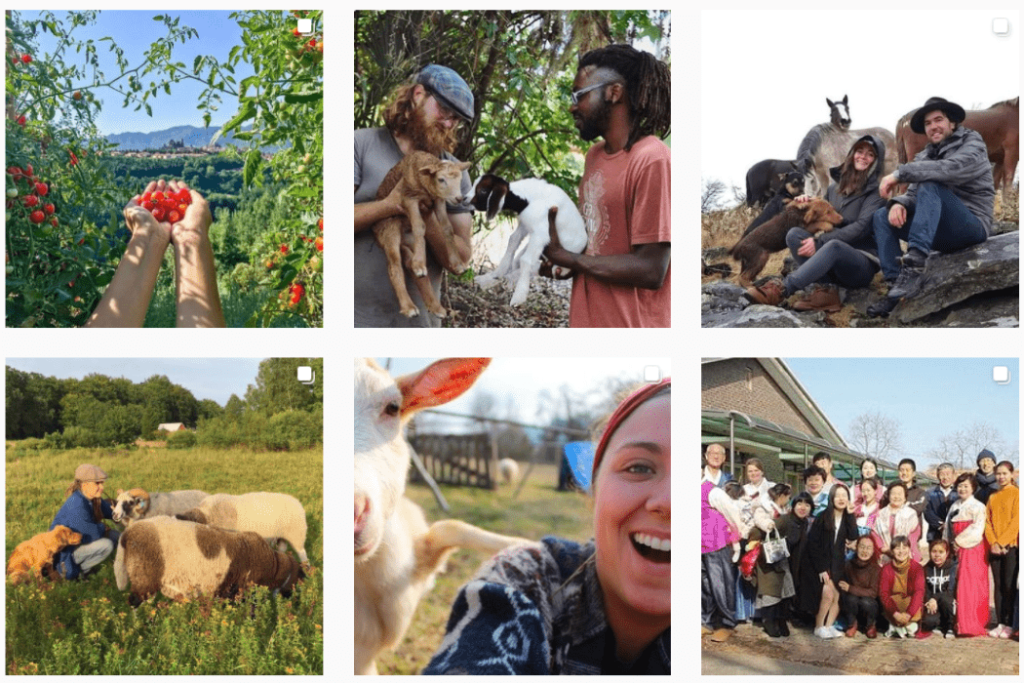

Featured image (top of post): Insta-worthy WWOOFing experiences; a screen capture from the WWOOF Instagram page.

About the author

Yana Wengel is an associate professor at the Hainan University — Arizona State University Joint International Tourism College. With interests that include volunteer tourism, tourism in developing economies, and mountaineering, Dr Wengel takes a critical approach to tourism studies. Yana’s dissertation examined the social construction of host-guest experiences in the World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) movement. Her current project is focused on tourism in mountain areas. Yana is interested in creative methodologies for data collection and stakeholder engagement. She is a co-founder of the LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® research community and an active practitioner of the Ketso tool.