Losing Lutruwita: Tourism troubles in Tasmania’s World Heritage wilderness

The World Heritage wilderness of Lutruwita (the palawa kani name for the island of Tasmania) is under threat from collusion between state government and private tourism interests, according to Tom Allen. The Wilderness Society campaign manager reckons tourism does best when it complements not compromises natural values. It’s a “Good Tourism” Insight.

Upon signing the Wilderness Act into US law in 1964, President Lyndon B Johnson said: “If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning.”

(Incidentally, President Johnson was also the first US president to recognise climate change, saying “This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through the steady burning of fossil fuels.”)

Since President Johnson made the Wilderness Act law, the world has seen catastrophic declines of wilderness, such that just 23% of the world’s wild areas remain.

Australia doesn’t have a Wilderness Act, nor does it have, I would argue, the same sense of respect for and celebration of wilderness as the US. But what it does have is some of the most intact, unspoiled, and incredibly beautiful wilderness areas left anywhere in the world, plus a lot of people who love these places; places like the Munga Thirri-Simpson Desert in the middle of the continent, takayna/Tarkine in Tasmania, and Kakadu in the Northern Territory, among many others.

Also see Erika Jacobson’s “GT” Insight

“Should it all be ecotourism? Reimagining travel & tourism in 2021”

Tasmania’s wilderness is the best of the best and …

Tasmania is the custodian of some of the richest, most unique, and superlative wilderness in the world. In fact, the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) fulfils more World Heritage criteria than anywhere else on Earth.

(Mt Tai in China also fulfils seven World Heritage criteria but only one of those relates to nature. Mt Tai has all six cultural criteria and one natural criterion, whereas Tasmania fulfils all four natural criteria and, thanks to rich Aboriginal cultural heritage, also fulfils three cultural criteria.)

Truly, Tasmania has the best of the best.

Wilderness is Tasmania’s biggest tourism attraction …

Reflecting its quality, Tasmania’s wilderness is the single most important draw card for the state’s tourism industry, the island’s biggest industry (pre-COVID).

“Tasmanian Wilderness is a major [tourist] attraction, and source of destination brand and appeal underpinning the Tasmanian tourism industry. The economic value of the TWWHA, from visitor spending alone, was estimated at [AUD] 721.8 million in 2007 – supporting approximately 5,300 jobs. Tourism Tasmania research has also shown that ‘wilderness’ is integral to Tasmania’s brand and appeal as a total tourism destination: ‘wilderness’ is the greatest trigger to influence intention to visit Tasmania, and respondents across market segments consistently rank ‘wilderness’ as having the highest appeal and being a uniquely Tasmanian experience.”

Yet …

Wilderness is lutruwita / Tasmania’s beating green heart ecologically and financially. So you might think that the state government would have a positive view of the island’s hugely-important World Heritage area.

But no. But rather than genuinely celebrating wilderness and protecting it with something like the Wilderness Act, the state has gone the other way.

The statutory management plan for the World Heritage Area has been weakened. Here’s a helpful comparison of the stronger 1999 Management Plan compared with the weakened 2015 one. The 2015 plan was specifically weakened to allow wholesale tourism developments throughout the World Heritage Area.

The government has a pipeline of 40 or so (no one really knows the exact number because it’s kept secret) trained on the TWWHA. If all these developments were to proceed throughout the World Heritage Area, the superlative, world-leading wilderness character would be gone forever.

We know this because the Wilderness Society Tasmania commissioned a wilderness impact assessment, which looked at the impacts of just one of the proposals.

Chopper in, chopper out

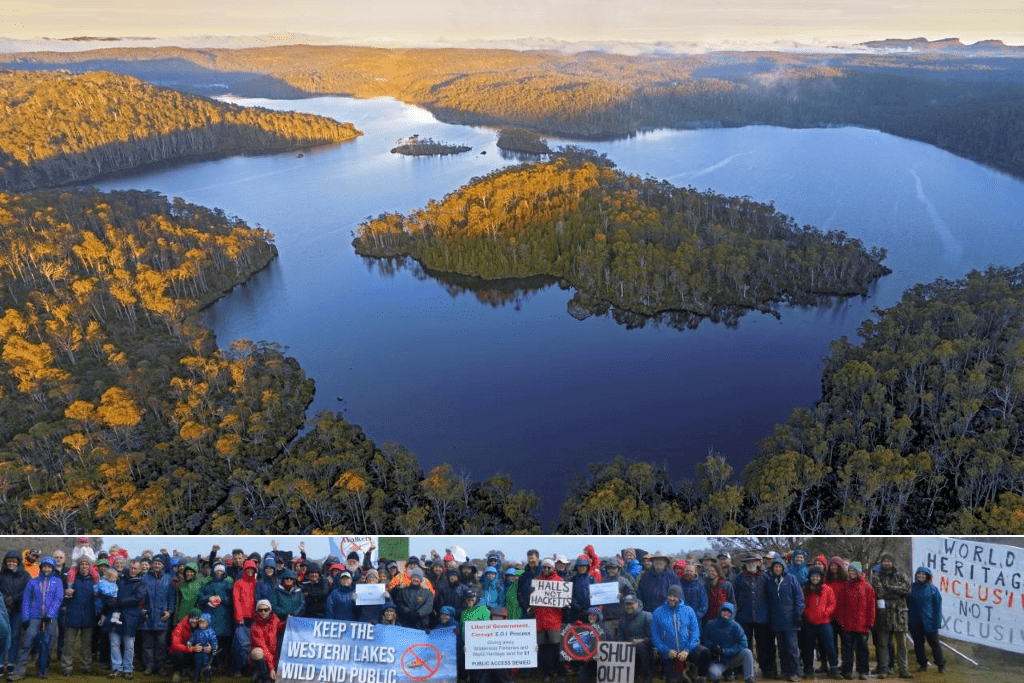

The proposal studied was that of luxury accommodation to be built on Halls Island on Lake Malbena in the middle of Walls of Jerusalem National Park, which is part of the TWWHA. Tourists would be flown in and out by helicopter. The report showed that the wilderness character would significantly decline if the proposal were to proceed, not to mention multiple other impacts on natural values.

Although it hasn’t been publicly released yet, the Commonwealth environment minister Sussan Ley MP has cited a Wilderness Quality Assessment by Tasmania’s Parks and Wildlife Service that found exactly the same thing. In fact, the impacts it predicts are worse than those in the Wilderness Society report.

The Parks and Wildlife report found that “a total of 4,200ha of land would have a reduction of Wilderness Quality” if the Lake Malbena proposal were to proceed. The mad thing is, Parks and Wildlife supports the tourism proposal that its own report found would degrade the wilderness it is charged with managing. Welcome to Tasmania!

Even though wilderness is the single-biggest attraction for visitors to Tasmania, the state government and the island’s peak tourism bodies support these developments. It’s hard to understand this ‘logic’. It would be perfectly possible to encourage nature-based tourism ventures to build their required infrastructure outside the TWWHA so that they don’t degrade the wilderness that attracts their guests and supports their business.

Also see David Gillbanks’ “GT” Events report

“Regenerative ecotourism: Asking questions is the best place to start”

They’re giving it away, but we’re fighting back

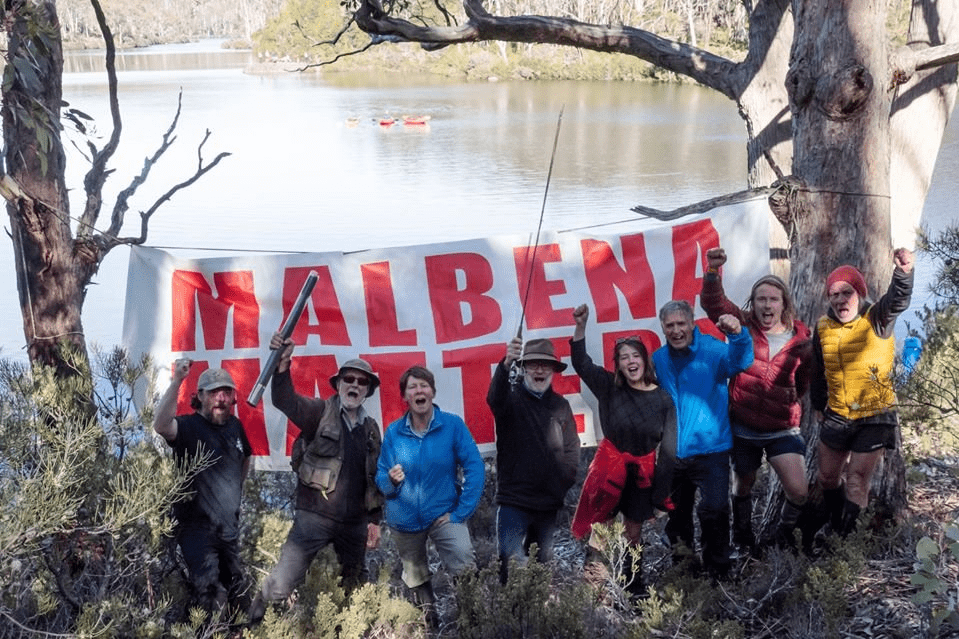

The controversial Lake Malbena proposal is the first cab off the rank of the Government’s 40 or so private commercial tourism proposals lined-up for the TWWHA. What they all amount to is a land grab; a transfer of public World Heritage land to private tenure from which vested interests can profit. The Lake Malbena deal has already affected longstanding public stakeholders. For example, members of the public who have for years been regular visitors to Halls Island have been barred.

Instead of selling or leasing the land at market rates, the State Government is handing it out for next to nothing. It costs more to rent a shop in Hobart than the AUD 6,000 [USD 6,690] annual rent being charged to the Lake Malbena tourism developers who are the new ‘owners’ of Halls Island. Compare this to the likely cost for an individual to stay at the proposed new development for three days; in the order of AUD 4,500 [USD 3,519].

We’ve undertaken legal action to stop this proposal from proceeding and are waiting for a decision from the Tasmanian Supreme Court. A coalition including the Wilderness Society Tasmania and the Tasmanian National Parks Association contested the planning application through the local council, then the State planning tribunal, and now the State’s highest court. We are arguing that a permit for this proposal would breach planning laws, including the State Nature Conservation Act 2002.

And we’re waiting for Australia’s environment minister Sussan Ley to open up public submissions on the proposal. To her credit, Ms Ley has determined that the proposal is a “controlled action” under the Commonwealth’s Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. This acknowledges the potential impacts of the development on a world-class natural environment. When submissions open, our focus will be to demonstrate the multiple ways that the proposal breaches the EPBC Act and the multiple ways that it breaches the statutory Management Plan for the TWHHA too. (If you’d like more information or to help, please get in touch: [email protected]).

The larger problem isn’t so much the single proposal at Lake Malbena, it’s the Tasmania State Government’s broader policy to “unlock the parks” to privatisation and development, which will degrade the very thing the people come to Tasmania to experience: its unspoiled wilderness.

Also see Nirmal Shah’s “GT” Insight

“From over- to no-tourism in Seychelles: What now for conservation?”

Conservation and tourism must work together

Our view is clear: conservation and tourism is at its best when we work together. That means protecting high value conservation landscapes and managing tourism that respects, protects, and celebrates ecological integrity. Especially at this time when so many regional tourism operators are struggling, the government should be supporting responsible tourism ventures in local communities instead of trying to develop away remote and pristine areas that everyone wants left intact in their own majesty.

Henry David Thoreau, another American, famously said: “In wilderness is the preservation of the world”. More recently, Sir David Attenborough, perhaps reflecting on the massive loss of wild places during his lifetime, said: “We must rewild the world”. Yet we in Tasmania, instead of being the world leader in conservation and nature tourism that we could be, needlessly risk undermining the very thing we are known for; our wilderness.

What do you think? Share a short anecdote or comment below. Or write a deeper “GT” Insight. The “Good Tourism” Blog welcomes diversity of opinion and perspective about travel & tourism because travel & tourism is everyone’s business.

Featured image (top of post): At the centre of a controversy is Halls Island on Lake Malbena in the middle of Walls of Jerusalem National Park, which is part of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA), Tasmania, Australia. Image by © Rob Blakers. And walkers and recreational fishers protest against helicopter access to Halls Island. Both images supplied by Tom Allen of the Wilderness Society Tasmania.

About the author

Tom Allen is campaign manager for the Wilderness Society Tasmania and has campaigned on the environment for more than 10 years.