Why tourism degrowth just won’t do after COVID-19

Among tourism academics and thinkers today — the outspoken ones at least — Jim Butcher is one of the few who would challenge the notion that post-pandemic tourism must — for the sake of the planet — be much diminished from what it was. He does just that in this “Good Tourism” Insight.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, much has been said and written about what the future holds for tourism. There are naturally discussions about adapting to social distancing, and measures to mitigate the disastrous situation facing the sector. And there are also debates about how the pause in tourism, and in the economy generally, open up the possibility to reconsider and reform tourism.

Thinking about reform is never a bad idea. However, it is not altogether clear why now, the middle of an economic disaster, is the best time to do this. Maybe a boom and the prosperity it brings creates better conditions for reform, as well as the resources to fund new ways of working.

Neither is it clear why the focus of many reformers — degrowth — is a good idea. Degrowth is the philosophical alternative that green campaigners and ‘critical tourism studies’ academics cohere around. They have pointed out that lockdown has facilitated seeing things in a different way. Car-free roads, country walks for the furloughed and home workers, and discovering one’s local community rather than contributing to airlines’ carbon emissions, are among the putative benefits of the crisis. There are some fair points to be made here.

But the premise of degrowth is that the economy, and tourism, have gone too far, too fast, and in too great numbers; the industry needs to scale down, and humanity should reign in its desire to travel. Degrowth assumes that mass tourism has left a damaging legacy for economies and culture as well as the environment. If it were implemented in a systematic way, degrowth would lead to disaster for the sector and those who derive a living from it.

Mass tourism has its problems, sure, and is often referred to now as “overtourism”. However, the lesson of COVID-19 is surely that “undertourism” is a far, far bigger problem. From Margate to Marrakesh, Miami to Massawa, the poor are hit hardest. The UN has predicted that COVID-19, or the response to it, could lead to hundreds of millions of people becoming impoverished. In fact the World Food Program points out that a “hunger pandemic” could eclipse the effects of coronavirus.

The figures are staggering. Some 130 million people are expected to join the 135 million who were already expected to suffer from acute hunger this year, bringing to 265 million the number at risk of starvation. Tourism and hospitality employment looms large in this. These industries rely on mobility and sociability, the two things that COVID-19 has undermined. They also rely upon gig and informal workers — a hand to mouth existence — to a greater extent than other industries.

Meanwhile, the degrowthers focus on overtourism and the need for an eco-centric “new normal” based on reduced economic activity, jobs and investment.

As I have argued elsewhere, what is needed is a recognition of the massive benefits generated by the global growth of mass tourism, both for tourists and host societies. That is not to whitewash the industry, or deny the very many attendant problems associated with overtourism. Rather, it is to look to expansive, growth-focused, future-oriented approaches to international leisure travel that were far more evident in the past.

Today, positivity and optimism seem at times to have been eclipsed by a declinist ‘holiday Malthusianism’ that sees leisure mobility mainly as a problem; rarely as a solution.

Our future, post-COVID-19, needs to relate to the material aspirations of people, as producers, to earn their living and improve their lifestyle. It should also recognise the universal desire, unfulfilled for the less prosperous majority, to enjoy the pleasures of tourism.

The low horizons of degrowth just won’t do.

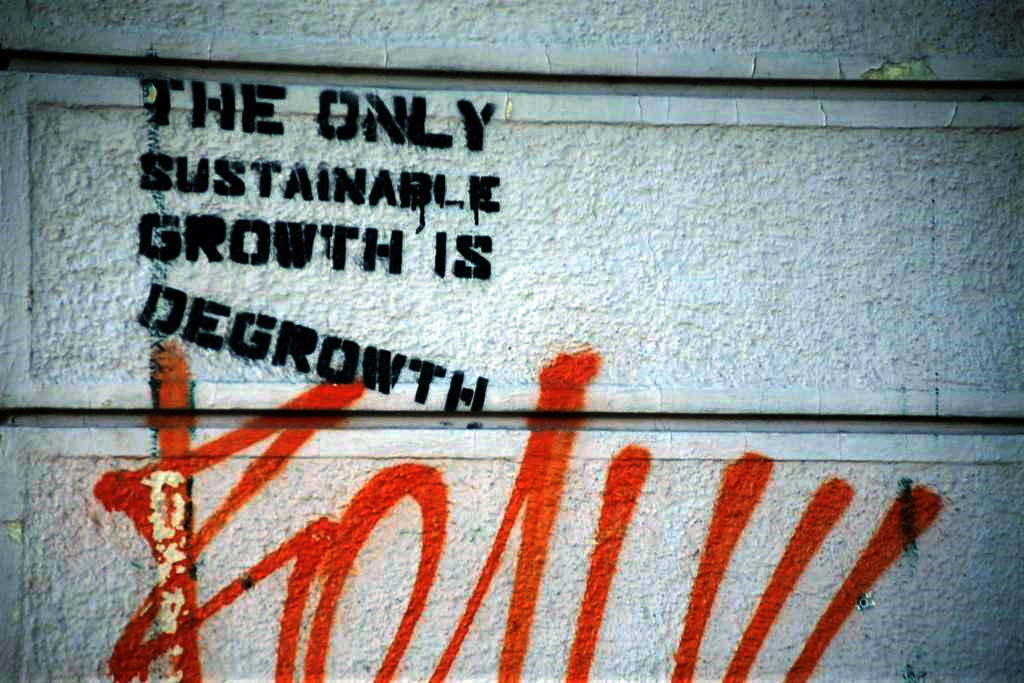

Featured image (top of post): “The Only Sustainable Growth is Degrowth”, according to this stencil graffito. Image by Paul Sableman (CC BY 2.0) via Flickr. “GT” ran a filter.

About the author

Jim Butcher is a lecturer and writer who has written a number of books on the sociology and politics of tourism and is now working on a book about mass tourism. Dr Butcher blogs at Politics of Tourism and tweets at @jimbutcher2.