Elephants are smart. What if tourism jobs were good for them?

Work, including offering tourists rides, is “not bad” for elephants — in moderation — so long as it takes into account the workload, stress, and welfare of each individual elephant, according to Dr Pakkanut Bansiddhi, Researcher, Center of Excellence in Elephant Research and Education, Chiang Mai University.

Dr Pakkanut revealed this at the Global Sustainable Tourism Council conference in Chiang Mai, February 28, much to the surprise of some, including “GT”. After the event, Dr Pakkanut kindly supplied “GT” with a summary of the main findings of six recent research projects that looked into elephant welfare in northern Thai camps (PDF).

Noting that the research took place against the background of poor general conditions for elephants and mahouts, there were more surprising findings:

Elephants that are ridden are less stressed …

“Elephants that participated in riding activities, with more work hours/day had better body condition and health measures.”

A main finding of “Article 4” in the download

Elephants that participated in saddle riding had lower overall fecal glucocorticoid metabolite concentrations (FGM — a stress hormone), glucose, and insulin levels, perhaps due to the positive effects of exercise.

A preliminary finding in an article still under review by journals

… than observation-only elephants

Elephants in the observation-only program had higher FGM levels compared to elephants that participated in work activities.

A preliminary finding from an article still under review by journals

Elephants in the observation-only camp had comparatively high FGM levels. They also had poor body condition and poor lipid and metabolic profiles, possibly related to less exercise and a diet high in calorie-dense supplementary foods such as bananas and sugar cane.

A preliminary finding from an article still under review by journals

“GT” asked Dr Pakkanut for her interpretation of the findings:

“We think it means that working and walking are enrichment activities for elephants that may guard against stress,” she replied.

“Elephants in the observation-only program do not walk much and spend less time with mahouts compared to elephants doing other types of work. So they may stress from limits on exercise and reduced interaction time with their mahouts.

“However, we found higher stress levels during the high tourist season. So, even if working and walking are good for elephants, we have to control their workload and the number of tourists encountered by each elephant.”

GT asked: “Were the elephants that showed higher FGM in the observation-only camps moved there in their lifetime? Would a new and unfamiliar lifestyle cause them stress? Would elephants born and raised in those conditions be better suited?”

Dr Pakkanut responded: “Most of them were at the observation-only camps for more than one year, so I don’t think this is acute stress from a new and unfamiliar lifestyle. Some elephants may be able to cope with longer term stress conditions but I don’t think all of them can. More studies are needed to answer and support my ideas.”

As Dr Pakkanut acknowledges, there is more research to do to get a clearer picture. Note, for example, the seemingly very small sample sizes for articles 4 & 5 and the fact that only one observation-only camp was included.

However, if these findings are proven to be correct by follow-up studies, it might mean that there are a lot of varied and meaningful tourism-related jobs that could benefit Thailand’s captive elephants.

Elephants are smart

Unemployment has negative consequences for the mental and physical well-being of human animals.

A “what if”: What if other intelligent and sentient beings like elephants also need something challenging and meaningful to fill their days?

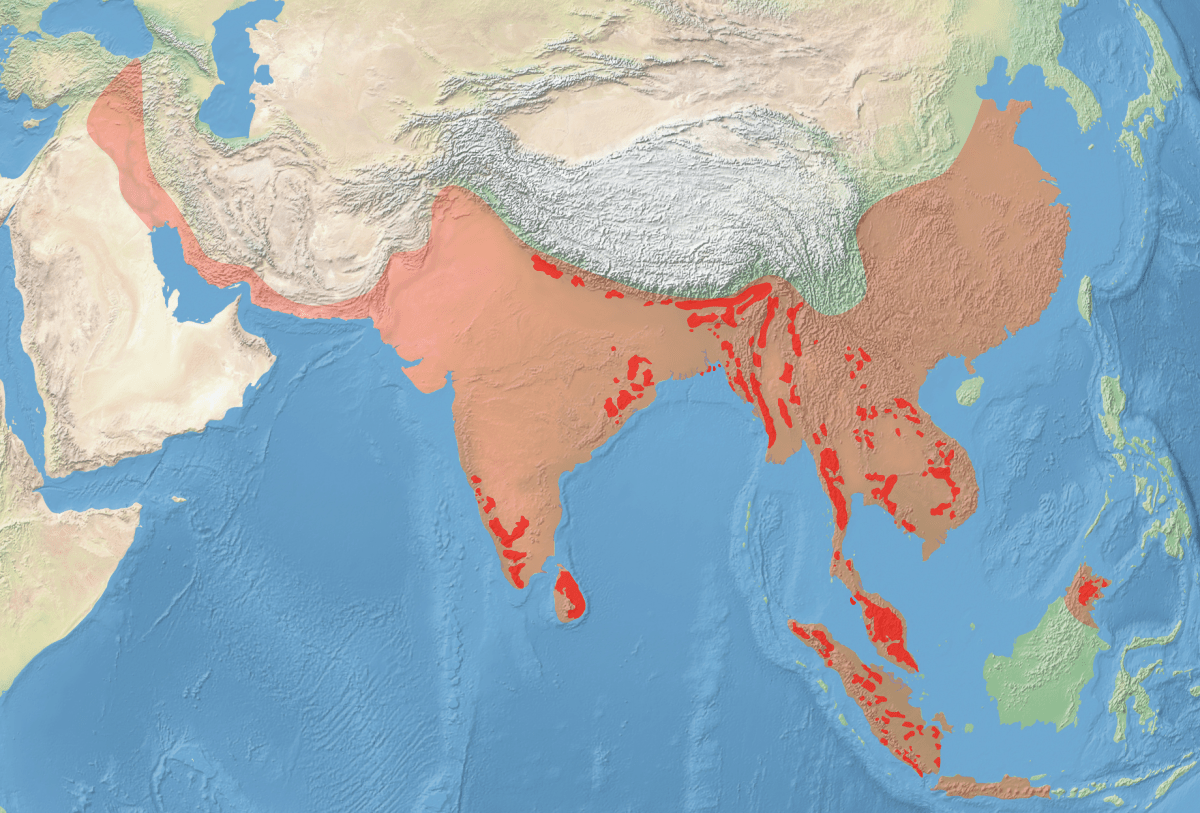

If we assume for the sake of argument that Dr Pakkanut’s research findings are backed up by further research, then what are the alternatives for elephants? First, there is not enough wilderness for the ideal scenario in which captive elephants are set free to roam unimpeded across their ancestral lands and engage in the challenging and meaningful work of survival. Second, simply existing within the limited land area of an observation-only camp eating the elephant equivalent of room service may not be worthy of the creatures’ potential.

More “what ifs”: What if training and employment by a benevolent tourism industry was the best outcome for elephants? What if it were undertaken transparently against a background of much improved general living conditions using contemporaneous best practices that were tailored to the personalities, talents, and interests of individual elephants? And what if it instilled greater levels of professionalism and pride among mahouts? Would that not be a good thing for both species?

Maybe there is a soft bigotry of low expectations — of elephants or humans (maybe both) — that assumes elephants cannot or would rather not find interest and meaning in productive work with and among humans. If there are low expectations of what’s possible, Dr Pakkanut doesn’t share them. She agreed with a proposition “GT” put to her, based on her research findings and this flight of fancy, that “elephants can benefit cognitively, psychologically, and physically by being positively challenged by their mahouts and interacting with humans”.

(Also read The New York Times article “Unemployed, Myanmar’s Elephants Grow Antsy, and Heavier”, January 30, 2016.)

But, training …

Elephant expert John Roberts contends in his “GT” Insight on “Elephant Tourism: The harms of received wisdom” that much of today’s populist concern about the welfare of captive elephants stems from when the barbaric practice of “crushing” their spirit came to light.

According to Mr Roberts, the torture associated with “crushing” has been incorrectly conflated with the Thai word “phajaan”, which “refers to a religious/spiritual ceremony performed before any training procedure”.

“This has been harmful because traditional trainers in the north all say that the phajaan is necessary to successfully train an elephant. Indeed a training team will perform a phajaan even if they’re about to attempt a fully positive reinforcement training session.”

Even if Mr Roberts is correct, it appears that in the wider world the word phajaan will forever be associated with old-school crushing. DuckDuckGo it and look at all the top results.

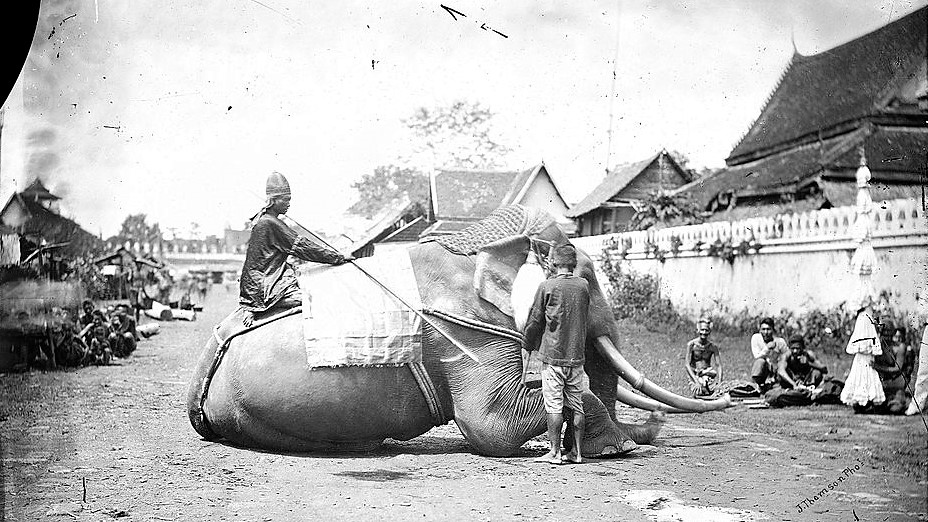

Crushing is a brutally efficient set of tactics for taming wild-caught calves that was widely implemented in Thailand and throughout Southeast Asia in an era when elephants were used as organic tractors, trucks, and tanks. For centuries — in agriculture, forestry, and other industries requiring brute strength, as well as for war in a region often riven by rivalry — elephants were prized beasts of burden.

According to Mr Roberts, Thailand’s international image was dealt a severe blow about 20 years ago when video footage of crushing techniques went viral. The footage is by no means the first nor most recent documented case of the worst practices — and there will likely be more — but it was the first to raise widespread awareness of crushing. This was positive because the international backlash forced the Thai government’s hand.

Traditions die hard in Asia — and so did a lot of young elephants at the hands of this particular one — but the Thai government made crushing practices illegal almost immediately. And, recognising that it would be difficult to enforce the law, the Thai government also ordered the Forest Industries Organisation — the government department with the most working elephants at the time — to develop and promote more humane training techniques.

The problem Mr Roberts has with the video is that it continues to be used to misrepresent today’s reality on the ground. It persists in various forms online — in remixes and samples — and is often presented as though it were the latest news. And it continues to elicit both understandable emotional responses and incomprehensible general condemnations of Thailand and the Thai people.

This highlights a couple of things: First, that the video is indeed distressing and hard to watch. Second, that those who continue to use the video to represent the current situation either: 1) need to do their homework, or 2) they use it to deliberately mislead people into joining their side of a complicated debate.

This is not to deny that terrible techniques are still used in some places. Criminals exist. Crimes happen. However, Mr Roberts would assert that the generally accepted and adopted practices for training elephants in Thailand are now focussed on reinforcing positives rather than crushing spirits — an evolution that his organisation, the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation, has help to spread in mahout communities across Southeast Asia for the past seven years.

The video below is from Myanmar’s “first ever” target training positive reinforcement workshop for elephants that took place in December 2015.

Dr Pakkanut said that she and her colleagues had not yet done any direct research into elephant training. For her latest thinking on the topic she pointed to a review article that she recently had published in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science:

A criticism of elephant tourism is that all elephants are harshly trained so they can participate in activities such as trekking, shows and painting. We do not dispute that inappropriate training methods are used at some venues; however, the extent is difficult to verify because there is no oversight, and training methods are left up to mahouts or owners (Rizzolo & Bradshaw, 2018). Without a comprehensive survey of training methods used in Thailand, based on extensive direct observations, this will remain a controversial topic.

Pakkanut Bansiddhi, Janine L. Brown, Chatchote Thitaram, Veerasak Punyapornwithaya & Korakot Nganvongpanit (2019): “Elephant Tourism in Thailand: A Review of Animal Welfare Practices and Needs”, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science

Perspectives

If the following additional findings from Dr Pakkanut et al’s recent research are accurate they would suggest to “GT” that the animal justice warriors of the west should maybe turn their attention to their own backyards first:

“Thai elephants had better BCSs (body condition scores) when compared to those from North American and UK zoos.”

A main finding of “Article 4” in the download

“The working bulls in this study had better body condition than those in western zoos elephants, which could be due to higher amounts of exercise.”

A main finding of “Article 5” in the download

Meanwhile, experts and researchers on the ground in Thailand should continue to make progress in better understanding elephants, evolving best practices, changing attitudes and habits in camps and among mahouts, and improving the overall conditions.

As Mr Roberts argues, without the support and oversight of “enlightened” travellers and tourists willing to visit elephant camps, spend their money, and ask the hard questions, progress will be a lot slower and much more difficult — if not impossible.

Dr Pakkanut and her colleagues are doing important field research that — for now and maybe only temporarily — validates what elephant experts like Mr Roberts have felt they have known for years. It also reminds us non-experts that we should not be so arrogant as to assume we know best.

Just as conditions are improving for many captive elephants, and just as they are being better understood by researchers employing the scientific method, the last thing elephants need is to be led down a road paved by animal welfare groups — with good intentions — to a brand new hell.

Featured image: A mahout feeding an elephant at the Elephant Nature Park, near Chiang Mai, Thailand. By Adbar (CC BY-SA 3.0) via Wikimedia.

Downloads

- Summary of the main findings of six research projects that looked into elephant welfare in northern Thai camps (onsite PDF).

- Pakkanut Bansiddhi, Janine L. Brown, Chatchote Thitaram, Veerasak Punyapornwithaya & Korakot Nganvongpanit (2019): “Elephant Tourism in Thailand: A Review of Animal Welfare Practices and Needs”, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, DOI: 10.1080/10888705.2019.1569522 (offsite paywall)

Disclosure by the author

I have no dog in this fight — and I don’t condone dog-fighting! I have NOT been paid to take part in this debate by any side. I am as concerned about the welfare of elephants as the next non-expert human. My only firm opinion on this issue is that it is complicated.