Why we are banning tourists from climbing Uluru

Climbing Uluru has always been discouraged by the park’s traditional owners, the Anangu people, however tourists continue to climb the rock on a daily basis. Sammy Wilson, Chair of the Park Board of Management, explains for The Conversation why his people have decided to ban the climb.

The Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Board has announced tourists will be banned from climbing Uluru, an activity long considered disrespectful by the region’s traditional owners.

Anangu have always held this place of Law. Other people have found it hard to understand what this means; they can’t see it. But for Anangu it is indisputable. So this climb issue has been widely discussed, including by many who have long since passed away. More recently people have come together to focus on it again and it was decided to take it to a broader group of Anangu. They declared it should be closed. This is a sacred place restricted by law.

It’s not just at board meetings that we discussed this but it’s been talked about over many a camp fire, out hunting, waiting for the kangaroo to cook, they’ve always talked about it.

The climb is a men’s sacred area. The men have closed it. It has cultural significance that includes certain restrictions and so this is as much as we can say. If you ask, you know they can’t tell you, except to say it has been closed for cultural reasons.

Tourists have previously used a chain to climb Uluru, but from 2019 the climb will be banned. Source: The Conversation.

What does this mean? You know it can be hard to understand – what is cultural law? Which one are you talking about? It exists; both historically and today. Tjukurpa includes everything: the trees; grasses; landforms; hills; rocks and all.

You have to think in these terms; to understand that country has meaning that needs to be respected. If you walk around here you will learn this and understand. If you climb you won’t be able to. What are you learning? This is why Tjukurpa exists. We can’t control everything you do but if you walk around here you will start to understand us.

Some people, in tourism and government for example, might have been saying we need to keep it open but it’s not their law that lies in this land. It is an extremely important place, not a playground or theme park like Disneyland. We want you to come, hear us and learn. We’ve been thinking about this for a very long time.

We work on the principle of mutual obligation, of working together, but this requires understanding and acceptance of the climb closure because of the sacred nature of this place. If I travel to another country and there is a sacred site, an area of restricted access, I don’t enter or climb it, I respect it. It is the same here for Anangu. We welcome tourists here. We are not stopping tourism, just this activity.

On tour with us, tourists talk about it. They often ask why people are still climbing and I always reply, ‘things might change…’ They ask, ‘why don’t they close it?’ I feel for them and usually say that change is coming. Some people come wanting to climb and perhaps do so before coming on tour with us. They then wish they hadn’t and want to know why it hasn’t already been closed. But it’s about teaching people to understand and come to their own realisation about it. We’re always having these conversations with tourists.

And now that the majority of people have come to understand us, if you don’t mind, we will close it! After much discussion, we’ve decided it’s time.

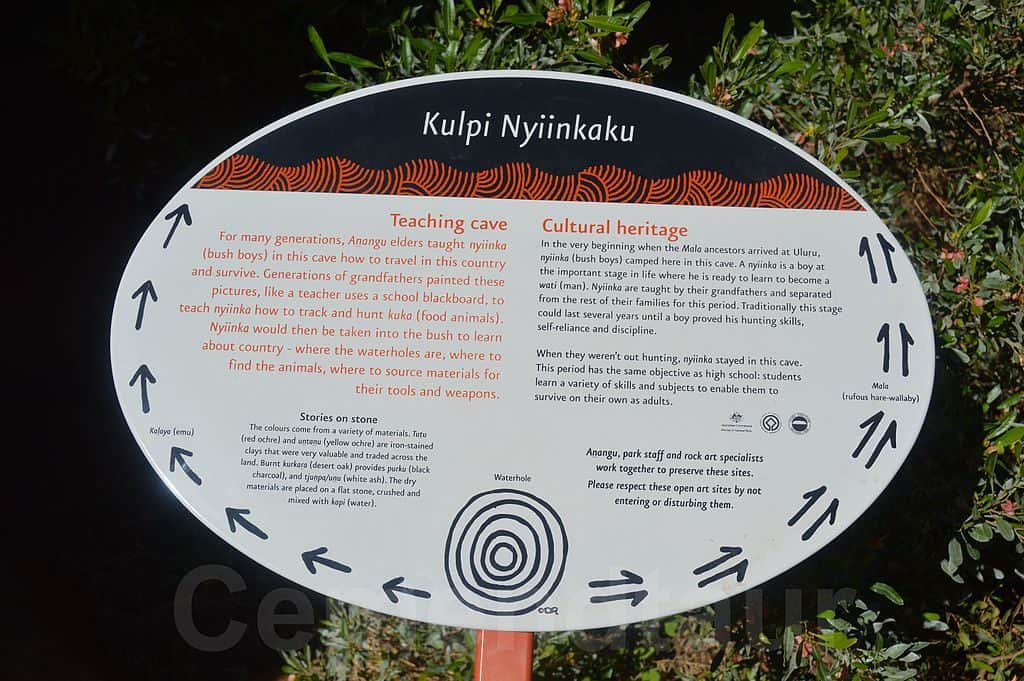

There is plenty to do and discover at ground level, preferably with an Anangu guide. Picture by Cemendtaur (CC BY-SA 4.0) via Wikimedia.

Visitors needn’t be worrying there will be nothing for them with the climb closed because there is so much else besides that in the culture here. It’s not just inside the park and if we have the right support to take tourists outside it will benefit everyone. People might say there is no one living on the homelands but they hold good potential for tourists. We want support from the government to hear what we need and help us. We have a lot to offer in this country. There are so many other smaller places that still have cultural significance that we can share publicly. So instead of tourists feeling disappointed in what they can do here they can experience the homelands with Anangu and really enjoy the fact that they learnt so much more about culture.

Whitefellas see the land in economic terms where Anangu see it as Tjukurpa. If the Tjukurpa is gone so is everything. We want to hold on to our culture. If we don’t it could disappear completely in another 50 or 100 years. We have to be strong to avoid this. The government needs to respect what we are saying about our culture in the same way it expects us to abide by its laws. It doesn’t work with money. Money is transient, it comes and goes like the wind. In Anangu culture Tjukurpa is ever lasting.

Years ago, Anangu went to work on the stations [livestock ranches]. They were working for station managers who wanted to mark the boundaries of their properties at a time when Anangu were living in the bush. Anangu were the ones who built the fences as boundaries to accord with whitefella law, to protect animal stock. It was Anangu labour that created the very thing that excluded them from their own land. This was impossible to fathom for us! Why have we built these fences that lock us out? I was the one that did it! I built a fence for that person who doesn’t want anything to do with me and now I’m on the outside. This is just one example of our situation today.

Sammy Wilson (right), Chair of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, at the 30th Anniversary Handback Festival in 2015. Source: AIATSIS.

You might also think of it in terms of what would happen if I started making and selling coca cola here without a license. The coca cola company would probably not allow it and I’d have to close it in order to avoid being taken to court. This is something similar for Anangu.

A long time ago they brought one of the boulders from the Devil’s Marbles to Alice Springs. From the time they brought it down Anangu kept trying to tell people it shouldn’t have been brought here. They talked about it for so long that many people had passed away in the meantime before their concerns were understood and it was returned. People had finally understood the Anangu perspective.

That’s the same as here. We’ve talked about it for so long and now we’re able to close the climb. It’s about protection through combining two systems, the government and Anangu. Anangu have a governing system but the whitefella government has been acting in a way that breaches our laws. Please don’t break our law, we need to be united and respect both.

Over the years Anangu have felt a sense of intimidation, as if someone is holding a gun to our heads to keep it open. Please don’t hold us to ransom … This decision is for both Anangu and non-Anangu together to feel proud about; to realise, of course it’s the right thing to close the ‘playground’.

The land has law and culture. We welcome tourists here. Closing the climb is not something to feel upset about but a cause for celebration.

Let’s come together; let’s close it together.

Read this again in Pitjantjatjara, the language of the Anangu.

This article by Sammy Wilson, Chair of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Board of Management, was originally published on The Conversation (CC BY-ND 4.0; the “GT” Blog used different images and added a little more information to the introductory paragraphs).

Featured image: Dawn view of Uluru with Kata Tjuta in the background. Enhanced image by Leonard G. via Wikimedia.

Related posts