The keys to managing growth and sustainable tourism governance

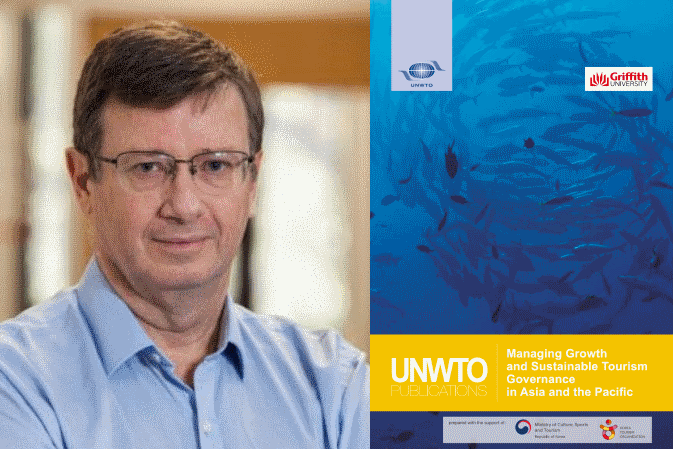

A special report on Managing Growth and Sustainable Tourism Governance in Asia and the Pacific was launched by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) at its 22nd General Assembly in Chengdu, China last week. For this “GT” Insight, David Gillbanks of The “Good Tourism” Blog corresponded with the lead author of the report Dr Noel Scott, to find out what the report is all about and what it can teach tourism stakeholders of all shapes and sizes.

“GT”: Congratulations on the launch of the UNWTO special report Managing Growth and Sustainable Tourism Governance in Asia and the Pacific. What is it all about?

Dr Scott: The key message from this report if that unless the institutions responsible for the task of maintaining the sustainability of tourism destination have the directive capacity and directive effectiveness to achieve this task then it will not happen.

The implication is that there is a need to understand the directive capacity and effectiveness of different institutions (government, community, NGOs, private sector, etc).

It is likely that individually, none of the organisations will have directive capacity and directive effectiveness to achieve the task of sustainable tourism destination development.

Therefore there is need for these organisations to work together by setting objectives, identifying their separate and joint responsibilities and developing the required directive capacity and directive effectiveness.

A number of cases in the special report illustrate these points.

“GT”: What is meant by “directive capacity” and “directive effectiveness”? I assume both are a combination of knowledge of problems and solutions, leadership, and authority. However when I plugged “directive capacity” into my favourite search engine it came up with links related to patient autonomy and living wills!

Dr Scott: Directive capacity is what an organisation can legitimately direct its member to do — its organisational powers. So first let’s think about two different types of institutions: religious faiths and private sector businesses.

Some religious faiths maintain the power to direct what a member of that faith eats, wears and their appropriate behaviour at certain times of day. Most private sector businesses cannot direct what their employees eat, but may have the right to direct what they wear and the appropriate behaviour during working hours. Religious faiths and private sector businesses have directive capacity over different types of personal behaviour.

Now think about government national park agencies. A national park agency is given powers to protect the long-term environment of a national park. However, a park ecosystem can be seriously affected by clearing of trees immediately outside its boundaries and the agency can do nothing. It has no directive capacity outside its boundaries.

BUT, what if the national park agency establishes a voluntary organisation of local landholders that commit to protection of the park? This new public-private partnership may agree a code of conduct and to limits on vegetation clearing. The members of this new voluntary organisation now have directive capacity to protect the park and its surrounds. This directive capacity is based on voluntary agreements amongst its members.

So directive capacity is the scope of powers that an organisation has to achieve some task (such as protecting a national park).

Now if we think about the directive capacities of government organisations in developing sustainable tourism destinations, we find that there are many organisations with directive capacities relating to sustainability but their roles and objectives often clash or conflict. In addition, a government may not have the powers necessary to restrict pressure on the environment by population increases, removal of vegetation or pollution of the water through inefficient sewerage systems.

“GT”: For the layperson (like me), can we refer to “directive capacity” as “authority” and “directive effectiveness” as “ability”? For example hotel GM (and “GT” Insight contributor) John Morris Williams has both the authority and ability, thanks to the buy-in and co-operation of his staff, to compost and recycle at Luang Prabang View Hotel. In this case authority would be meaningless without the co-operation of others. However, while he doesn’t necessarily have the authority (and certainly not the ability on his own) to pick up litter around the town of Luang Prabang, he is able to make that happen by forging co-operative partnerships with other stakeholders. In this case a lack of authority isn’t an obstacle thanks to co-operation.

Dr Scott: Essentially yes. Directive capacity means what authority Mr Williams has over completion of a task such as recycling, over whom Mr Williams has authority (his employees), how decisions are made — Are there discussions with employees or just Mr Williams making decisions by himself? Does his Board of Directors need to get involved? — so it’s a bit more well-defined than just saying Mr Williams has authority. It’s the same with “directive effectiveness”. This covers Mr Williams’ knowledge and skills, as well as his company’s time and money available, his ability to know the recycling has been done effectively and that he has achieved his objectives, and so on. The directive capacity and effectiveness of a small business is easier to understand because these are mostly straightforward and similar for all private businesses. The directive capacity and effectiveness of a government department is more difficult to measure.

“GT”: In the special report, governance is defined as a combination of directive capacity and directive effectiveness, which is illustrated by a matrix that has the former on the x‑axis and the latter on the y‑axis. Good governance is an attribute that can be ascribed to an entity that scores highly in both. The principle must surely scale up from the context of an individual in their household and community, through an organisation in its operating environment, all the way to a global player like the UNWTO itself. (Where would you place the UNWTO on this matrix!?)

So based on the 18 case studies that made it into the report, what specifically is the secret to good governance? The ability to build consensus and forge alliances certainly. How much is that dependent on a clear vision for the future and SMART objectives along the way?

Dr Scott: Yes, the same principles to all organisations. The UNWTO is an intergovernmental agency and like many of these, has no directive capacity (authority) regarding the task of achieving sustainable tourism. It can provide expert advice and recommendations to its member countries but that does not mean they have to implement them. The UNWTO does have significant expertise, knowledge and skills in providing advice on aspects of sustainable tourism but must work though other governmental organisations, which have more or less directive capacity.

The first key to good governance is to clearly define the task to be achieved. One problem with improving the sustainability of destinations is that what to do is poorly defined and hard to measure. Therefore it may be better to start with a specific task whose outcome is measurable. This could be a rubbish clean-up day, or the creation of a new national park. For some tasks it may be within your own capacity to organise, while other tasks will require a coalition of members with various levels of directive capacity and effectiveness.

The second key is to build consensus and trust, and this may take time. Sometimes small wins will provide a useful basis for development of further directive capacity or effectiveness.

Third, many of the cases were successful because of a champion, who created a coalition, or contributed new resources.

So good governance is partly about rules and laws and partly about people able to work together.

“GT”: A hypothetical. You wake up tomorrow morning with all the directive capacity in the world to make a start on sustainable tourism. You take your own advice by starting with a specific task whose outcome is measurable in terms of it shifting the global tourism industry toward sustainability. What is that task? How do you sell that as a priority to the industry? How do you deal with dissenters?

Dr Scott: Interesting. Well if we are talking unlimited directive capacity, then what you are saying is that I am able to require governments to develop laws that government agencies will implement. Good.

So I would select a particular destination: for example Labuan Bajo, home of the Komodo Dragon and a must-see destination in Indonesia that is developing quickly. Or perhaps Raja Ampat in West Papua.

I would then develop a plan in conjunction with local businesses to increase the cost of visiting these places significantly. In essence I would improve the value of the visit by better marketing, improved services and so on. At the same time I would develop and enforce a physical land use plan that restricts any new development to certain areas only, requires licences for entry of fishermen or business operators into national parks (similar to Great Barrier Reef Marine Park). I would also develop a program to ensure that new businesses had some local ownership component. If possible I would also restrict migration to the area perhaps through restrictions on new accommodation? The key is to be able to restrict supply of tourism services and residential/ business land use and attract a less price-sensitive market.

The end result would be the protection of a unique environmental resource with increased expenditure per visitor and a greater proportion going to local people. It would also mean that there was less pressure on the environment caused by a rapidly increasing population.

The problem with this scenario is that governments do not want to, or do not have the directive capacity to undertake it. In addition, I would sell it to the industry by saying that although it will take longer to undertake, it also means that they will have less competition in the longer term and not face unsustainable competition. I think that a local tourism business person may want this.

About Noel Scott

Noel Scott is Professor and Deputy Director at Griffith Institute of Tourism (GIFT), Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia. With research interests including the study of tourism experiences, destination management and marketing, and stakeholder organisation, Dr Scott has supervised 20 postgraduate students to successful completion of their theses. Dr Scott is a frequent speaker at international academic and industry conferences, has more than 210 academic articles published including 11 books, and is on the Editorial Board of 10 journals. He is also a Fellow of the Council of Australian University Tourism and Hospitality Educators and also of the International Association of China Tourism Scholars. Prior to starting his academic career in 2001, Noel worked as a senior manager in a variety of leading businesses including as Manager Research and Strategic Services at Tourism and Events Queensland. He earned his PhD in tourism management from the University of Queensland in 2004.

![The keys to managing growth and sustainable tourism governance 6 Professor Valeria Minghetti: "[B]e curious. Never stop asking yourself questions. Curiosity and the desire to find solutions is what makes a difference ..."](https://www.goodtourismblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Professor-Valeria-Minghetti-300x225.jpg)