Green Games for a blue planet? Rio 2016 one year on

Sustainable business consultant Ariane Janér witnessed first-hand how the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games affected the Brazilian city she calls home. In this “GT” Insight, Ms Janér reflects on Rio 2016 and summarises its potential, positives, broken promises, and missed opportunities.

One year has gone by since the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, promoted as the “Green Games for a Blue Planet”. It is a good moment to look at what it has meant for the host destination, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in terms of tourism and sustainability. As much has already been written about the Rio Games, let´s put things into context.

How and when did Rio de Janeiro, Brazil win the Games?

Rio de Janeiro barely made the shortlist for hosting the 2016 Olympic Games. With an overall score of 6.4, it was rated 4.5 for Safety and Security and only scored 6 or more for Government Support, Experience and Olympic Village.

But when Rio made the shortlist in 2008, the economy was booming and Brazil had achieved the coveted “investment grade” status from the major credit rating companies. Together with a good campaign (“Green Games for a Blue Planet”), and an emotional appeal to hold the Olympics in South America for the first time, Brazil won over the delegates in 2009.

The Economist celebrated Brazil’s stepping onto the world stage with the cover “Brazil Takes Off”.

Were the Rio Games expensive to host?

A 2016 Oxford Saïd study scrutinized the direct expenditures for the organization and sports venues for 19 Olympic Games since 1960. In their analysis, Rio 2016 cost less than recent Games with around US$ 5 billion (R$ 17.4 billion) in direct expenditures. This was much lower than Sochi 2014 (US$ 22 billion) and London 2012 (US$ 15 billion). The cost overrun for Rio was about 70%, which is quite good as Olympic Games go. Nearly half of Olympic Games have cost overruns of more than 100% and the average is 176%!

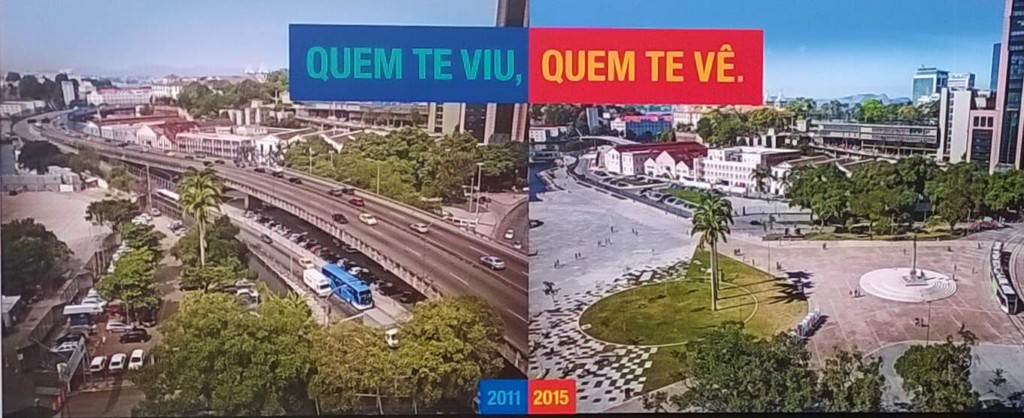

As with Barcelona 1992, investment in an urban redevelopment legacy for Rio’s citizens was higher than the direct event-related expenditures. More than US$ 7 billion was spent on upgrading Rio de Janeiro’s urban infrastructure. A large part of this went to improving urban mobility through an expansion of the public transport network. The other major investment was revitalizing the Rio Waterfront though a Public-Private Partnership.

Was it all public investment?

No, not all of this was public investment. The official data says that about 60% of the financing of the direct expenditures came from private enterprise (e.g the Olympic Village).

For the infrastructure legacy the numbers are more difficult to gauge, but the available data indicate that about 40% was private investment.

Not included in the numbers is the significant private investments made in increasing hotel capacity (estimated at US$ 3 billion) and small business investment.

Economic legacy: Mobility and urban upgrades

The main investment was in transport mobility: an extension of the metro, long distance rapid bus transit (BRT) corridors, a modern tram for the center and waterfront of Rio, and the easing of some road traffic bottlenecks. This has indeed improved transit times and transport options in Rio de Janeiro, which can be verified in the TomTom Traffic index.

Rio’s Waterfront (Porto Maravilha) has undergone a major face lift, much like Barcelona. From an ugly place to be avoided, it has become a major attraction for both visitors and locals, with museums, a Marine Aquarium (AquaRio), a pedestrian boulevard lined with giant Kobra murals, and refurbished warehouses, where the presence of food trucks and the staging of events are stimulated. And, of course, there is now a magnificent view of the Guanabara Bay.

Rio did not splurge on iconic sports venues like Beijing. Some of them were temporary with the view to using them as school buildings after the Games. Others were meant to be operated by private enterprise through a concession.

However, all these investments are yet to give returns. Due to the financial crisis in Rio de Janeiro, it is difficult to find sponsors and investors at the moment. So, for now, the maintenance costs for sports venues are borne by the city, which cannot afford this.

Not all suppliers to the Olympic Games have been paid. And many apartments in the Olympic Village, a private investment, still need to be sold.

The number of hotel rooms available went from 29,000 to 56,000, but occupancy rates are now low, especially for those constructed in new areas. Currently hotels are struggling to make an operational profit.

The number of rooms offered through AirBnB and similar sites soared. This included rooms in favelas (Portuguese for “slum”; informal urban area).

Environmental legacy: Greenwashing galore

Rio 2016’s sustainability program received ISO 20121 (Event sustainability management systems — Requirements with guidance for use) certification, after a third-party audit. These and other achievements are proudly paraded on the official Olympics website.

The Games’ opening ceremony echoed the vision of “Green Games for a Blue Planet”. The threat of climate change was highlighted by showing the effects of rising sea levels, the Olympic rings were shown in a formation of trees, and every athlete was invited to plant a tree to offset the carbon footprint of the games.

But, in reality, many green promises made for the first Olympic Games in South America and in the tropics were not delivered.

Most prominent in the media was the promise to clean up Guanabara Bay; reduce its pollution levels by 80%. This was an impossible task from the outset, as this meant coordinating with all the municipalities who were leaking sewage and solid waste into the rivers that flowed into the bay. And there was no money to invest. Some palliative measures were taken.

Rio de Janeiro’s main open landfill (Gramacho) which leached into the bay was closed and replaced by a slightly less impacting one (Seropedica) in 2012. More efforts were made to recycle municipal waste, but the rates are still very low. The Games’ main focus was on waste reduction.

One controversial decision was allowing a new Olympic Golf Course to be constructed in an environmental protection area instead of using an existing golf course. This decision favored a private real estate investment and the golf course was marketed as an environmental improvement.

Carbon emissions for the Rio Olympic Games were calculated at 3.6 million metric tons. Dow Chemical pledged to offset 2 million metric tons through GHG reduction. Better transport mobility and the sustainable design of venues would translate into lower emissions. The remainder would be offset by tree planting projects directed at restoring Atlantic Rainforest. Until now only 5 million of the 24 million seedlings have been planted and the reforestation companies are complaining about not receiving their money.

Was there a social legacy?

Though the Games were presented as inclusive, they failed to deliver for the poorer citizens.

More than 4,000 families were relocated for reasons related to the Olympic Project, like sports venues and bus and highway trajectories.

The Favela Pacification Program which started in 2008 meant that those living in favelas saw a reduction in violence due to better policing. In general crime rates in Rio de Janeiro went down. But the promises to follow this up by significant investment in sanitation, health and education were not kept. And now, with a financial crisis, there is not even enough money to pay for policing. Crime and violence in Rio de Janeiro are sharply up since the Olympics.

Lots of temporary jobs in construction were created in the run-up to the Games. However the financial crisis means that unemployment is sharply up again, also fueling crime.

The Deodoro Olympic Center was planned to be one of the legacies for a poorer part of the city. It would become a public park where radical sports could be practiced with a capacity to receive 6,000 visitors. For now the site is abandoned. Even the “forest of the athletes” still needs to be planted there.

Brazilian athletes had hoped that the Rio Games would leave a legacy for sports in general, through investment in training and sports facilities and more sponsorship opportunities. This has not materialized.

Did the Games boost tourism to Brazil?

No. This comes as no surprise, as there are plenty of studies that show that Olympic Games and other mega events do not boost tourism. The surprise is that organizers still use the argument.

In 2007, Brazil received 5 million international visits, of which 38% were from regional (South America) and 62% were long haul. In 2016, Brazil received 6.6 million international visits, of which 57% were regional and 43% were long haul. The annual growth rate for Brazil during that period was lower than the global rate. The number for 2016 is also well below pre-Games projection of 8.9 million foreign visits for that period.

This is bad news for the investors in the hotel industry in Rio de Janeiro. Room capacity is double that of 2007 and many hotels are now making operational losses.

Did the Games boost Brazil´s image as a sustainable destination?

Brazil started out with a positive image. But with eyes of the world on Rio de Janeiro, this started to unravel. Street protests, the impeachment of a president, major and ongoing revelations about corruption (including related to the Olympics), a growing financial crisis, the Zika virus, and the pollution in Guanabara Bay became major world news stories.

The Games themselves were a success, though. The transport mobility system with rapid transit buses and metro whizzed spectators to the venues. Helpful volunteers assisted the visitors, and the army was out in the streets to deter crime and terrorism. The sport was spectacular and the atmosphere in Rio de Janeiro was festive.

But no sooner had the last visitors left the mood turned sombre. Brazilians and cariocas (citizens of Rio) had to continue on amid a deepening financial and political crisis. Some key people involved in hosting the Olympic Games are now in jail, indicted or under suspicion of corrupt practices. Reports of abandoned venues and unfulfilled promises dominated positive articles in the media.

The efforts of UNEP to highlight sustainable tourism initiatives in Rio and elsewhere in Brazil failed to get much attention or support.

In the analysis of the World Economic Forum, Brazil’s Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Score went from 4.3 out of 7 (#59 out of 124 countries) in 2007 to 4.5 out of 7 (#27 out of 136 countries) in 2016. But this is not the progress it seems to be. Brazil´s score is based on its potential: natural resources (#1) and cultural resources (#8). Its score rose mainly because of two things: price competitiveness (its currency lost value) and tourism service infrastructure. However WEF ranked it #117 in “sustainability of travel and tourism development”.

So was the Games worth the effort?

It is still too early to say what the lasting legacies of the Rio Games will be. Only the Los Angeles Games in 1984 made an immediate profit. Hosting the Olympic Games in Rio did mobilize people and resulted in improvements for the city. It was also not the cause of Brazil’s financial crisis; merely another vanity project tainted by overspending and corruption.

But, sadly, the Rio Games highlighted that sustainable destination management is still not taken seriously by those in charge of mega-events. Environmental and social planning are seen as small appendices to conventional economic interests, not as important drivers of innovation, integration and inclusion.

Barcelona, the city that Rio de Janeiro tried to emulate, also invested big in infrastructure. It also went heavily over-budget (266% over according to the Oxford Saïd study). But Barcelona did clean up its rivers and did a better job of integrating the city. Today it is one of the most popular city destinations in the world, receiving more foreign overnight visitors than all of Brazil. (Ironically, it is now struggling with “overtourism”.)

Meanwhile, the International Olympic Committee has learned an important lesson. The buildup and aftermath of Rio de Janeiro and the withdrawal of cities like Boston, Rome, Budapest and Hamburg for the 2024 Games demonstrated the need for a less expensive bidding process and organization of the Games.

Paris and Los Angeles, the only interested bidders left, will now host the 2024 and 2028 Games respectively. They seem to be well positioned to make efficient use of existing and temporary resources to deliver less costly mega-events. And maybe they will discover a way to make the Games truly sustainable.

Featured image (top of post): From the opening ceremony of the 2016 Olympic Games in Maracanã Stadium, Rio de Janeiro. By Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil (CC BY 3.0 br) via Wikimedia.

About the author

Ariane Janér is a Dutch zoologist with an MBA who has been working in sustainable development and tourism in Brazil since 1991. She is active both as a consultant and through NGOs and has worked on various types of projects: From community-based tourism to sustainable procurement for private enterprise; from designing tours to writing business plans. Ariane is also a founder of the Global Ecotourism Network. Ariane Janér on LinkedIn .