And now for the weather: info-seeking & climate change adaptation in Pacific tourism

Climate change adaptation is increasingly talked about in the travel & tourism trade media as vital to the sustainability of the sector, especially in regions susceptible to extreme weather events and the worst-case scenarios of sea level rise, such as Pacific Island nations. In this “GT” Insight, Dr Johanna Nalau, Research Fellow at the Griffith Institute for Tourism and Griffith Climate Change Response Program, Griffith University, Australia, explains the findings of her study of weather information-seeking among Fiji tourism operators and what the possible implications are for climate change adaptation.

Understanding differences in the info-seeking behaviour of tourism operators

In the Pacific Islands, long white sandy beaches with iconic sunsets are often the main tourism attraction. Other attractions include pristine environments, coral reefs and marine life. The same weather and climate that enables the tropical environments to flourish is however also prone to cyclones and extreme events. The tourism industry bears often the brunt of adverse weather with decreased tourist arrivals and loss of business continuity.

Information clearly has a business value in that better information can help in making timely and even foresightful decisions on when to close down an operation and how to plan for expected business disruptions. As in our modern age most information is available through different kinds of media (TV, radio, internet), one would expect people to be able to access information relatively easily. Yet, often this is not the case. So what does impact on how tourism operators seek information?

How people differ in seeking, accessing and using information

We were curious about the factors that could explain differences in accessing, seeking and using weather and climate information among tourism operators in Fiji. We conducted a social science study in towns of Nadi and Suva in Fiji with both large and small tourism operators, and other tourism stakeholders. What we found was fascinating: people differed greatly in how they access weather information, who they trusted the most as a relevant source, and why they needed weather and climate information in the first place.

In our analysis three distinctly different groups emerged, which held in common particular factors for their behaviour:

Independent information seekers

The first group, “Independent Information Seekers” were individuals with high positions of responsibility in the organisation, and always with long-term experience with weather professionally. These individuals felt very comfortable in interpreting weather phenomenon by themselves, and they had often multiple websites and apps running at the same time on their computers and phones. For this group, it was very important to be on top of the situation, and distribute their analysis also to others who were dependent on their decisions for example regarding the evacuation of marinas.

Mediator-dependent information seekers

The second group, “Mediator Dependent Seekers”, were often managers who did not know necessarily which sites to go to and where to get the best information. They could sometimes call their relatives back in Australia or New Zealand and ask for weather updates as the Australian and New Zealand weather information seemed more accurate. This group of managers did not have high level of information literacy skills (how to navigate sites in the internet or which apps to download and use on their phone). This group was more comfortable in being informed by another person whom they trusted.

Observation-based information seekers

The third group, “Observation Seekers”, were more focused on observing the weather either based on their past experience of the place or by traditional knowledge signs that they had been taught in their community. The indigenous Fijians did not rely on usual media (TV, radio, internet) but, for example, read star formations and the way clouds were moving. Often this kind of knowledge is held within communities and people collectively discuss what particular signs might mean and then interpret the weather.

The kind of information in use

The operators used weather information daily, for the most part, depending on the nature of their operations. The active information seekers used a broader variety of information, whereas the mediator-dependent seekers mostly used TV, radio and official channels.

We also found that although many operators did not use longer-term climate information, many operators would welcome better and more consistent information at a seasonal scale so that they could do some forward planning. For example, it could be helpful to know the timing of rain periods for next business year and whether there are potentially drier and hotter periods in the next two-three years. If there is a marked increase in extreme events, such as cyclones, then better predictions could encourage activities such as cyclone-proofing tourism infrastructure.

Engaging the tourism sector in information use and access

So what does all this mean for the tourism sector and people’s planning and decision-making? One take-away message clearly is that if we want to support the sector and provide ‘useful’ information about weather and climate, we need to first understand the audience. If we do not know how people access weather information, extreme weather alerts, and why they trust particular sources, it is difficult to be heard. In many cases this may not matter, but there are situations in which timely and accurate information is life- (and business-) saving.

In Fiji, the existing relationships between the Fiji Hotel Association, Fiji Meteorological Services, NaDraki Weather Service, and the many operators could be enhanced to provide tailored training that responds specifically to the need of the tourism sector. This could even start from discussions around information literacy, promotion and awareness of accessible information and its interpretation.

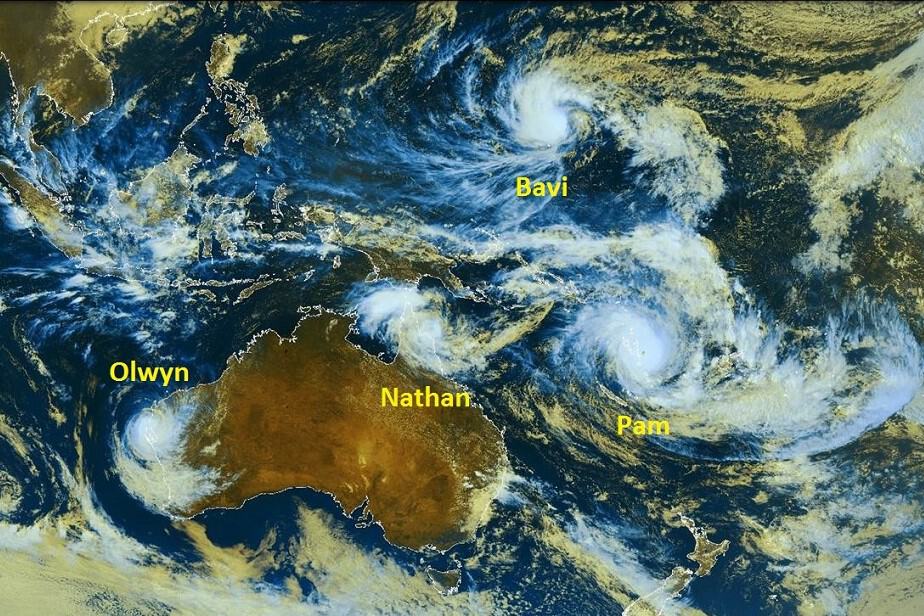

Featured image: Pacific Ocean, February 1, 2016. Four named tropical cyclones existing simultaneously in Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)‘s area of responsibility. From left to right: Tropical Cyclone Olwyn, Tropical Cyclone Nathan, Tropical Storm Bavi, Tropical Cyclone Pam. Source: US Navy via CHIPS.

About the author

Dr Johanna Nalau is a Research Fellow at Griffith University in Australia (Griffith Climate Change Response Program (GCCRP) and Griffith Institute for Tourism (GIFT)). She is passionate about broadening our understanding of how people make decisions about climate change adaptation and what information is most effective in that process, including the tourism sector.

Dr Nalau’s research is very focused on two things: theory and stakeholders in the real world. She has a keen interest in exploring this persistent gap between what we know in theory about adaptation and what we actually do about it, and has explored this topic from a social science perspective in Australia, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Zanzibar (Tanzania), Fiji and, most recently, Samoa.