Lynx between a species’ reintroduction & ecotourism?

So says the Lynx UK Trust, which last week updated stakeholders on its proposed trial reintroduction of the Eurasian lynx to the Kielder Forest of Northumberland in northern England.

According the the Trust, the Eurasian lynx is a native of the British Isles that was “forced out of much of Western Europe by habitat destruction and human persecution over the last 2,000 years”.

“The last of the British lynx disappeared around the year 700.”

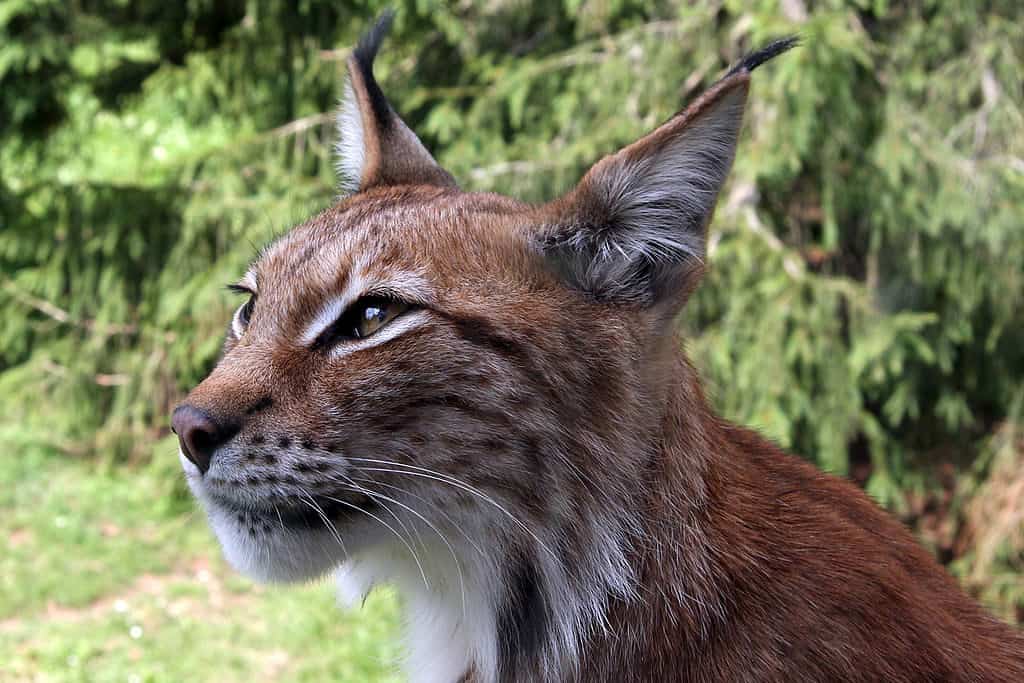

The medium-sized cat preys on “deer species and a variety of smaller mammal” and is “known by ancient cultures around the world as a mysterious ‘Keeper of Secrets’ that rarely leaves the forest”.

“This solitary and secretive nature means that they present no threat to humans and it is exceptionally rare for them to predate on agricultural animals.

“Their presence will return a vital natural function to our ecology helping control numbers of deer and a variety of agricultural pest species whilst protecting forestry from deer damage caused by overpopulation.”

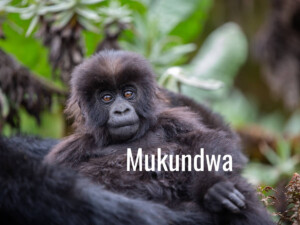

A Eurasian lynx kitten. By Bernard Landgraf, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia.

A “moral obligation”?

According to a report by The Guardian, the Kielder forest was chosen for the trial “due to its abundance of deer, large forest area and the absence of major roads”.

The six lynx to be released — two young adult males and four young adult females — would come from Sweden, where the species thrives. All six cats would have GPS collars reporting their location at all times.

Nevertheless, some locals are opposed to the reintroduction. Speaking on behalf of sheep farmers in the area, National Sheep Association CEO Phil Stocker, said: “Even if compensation were offered, it will not make sheep mortalities acceptable. I cannot see how distressing attacks caused by a wild animal will be accepted.”

However, Dr Paul O’Donoghue, chief scientific advisor to the Lynx UK Trust and expert adviser to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) told The Guardian: “You will never see a lynx running across an open field chasing down prey – they can’t do it. They are the epitome of a forest specialist – their coat is dappled.”

O’Donoghue says there is a “moral obligation” to reintroduce lynx: “We killed every single last one of them for the fur trade. That’s a wrong we have to right. Lynx belong here as much as hedgehogs, badgers, robins, blackbirds.”

On the potential for ecotourism, O’Donoghue said lynx would “generate tens of millions of pounds for struggling rural UK economies”.

A Eurasian lynx at Skåne Zoo, southern Sweden. By David Castor via Wikimedia.

“Lynx have already been reintroduced in the Harz mountains in Germany,” he said. “They have branded the whole area the ‘kingdom of the lynx’. Now it is a thriving ecotourism destination and we thought we could do exactly the same for Kielder.”

However if the lynx were to be reintroduced it would be very difficult for ecotourists to actually see one of the nocturnal cats.

“Lynx are very secretive and elusive, but that’s completely irrelevant,” O’Donoghue said. “It’s a chance to walk in a forest where lynx live, a chance to see a lynx track, to see a lynx scratching post. And if you did see a lynx in the wild, it would be the wildlife encounter of a lifetime.”

Community consultation

In an open letter (Facebook post) to the community of the Kielder Forest region dated July 6, the Trust explained: “11 months ago we held our first consultation meeting in Kielder Community Hall, to present our thoughts on a potential trial reintroduction of Eurasian lynx in the Kielder region, and to hear some initial reaction to it. Since then hundreds of you have spoken to us …”

The Trust’s consultation on the potential trial has finished and the “communication has been gathered into our various reports and submissions for the statutory agency, Natural England, to shortly consider”.

Eurasian lynx in Wildpark Leipzig. By Ad Meskens, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia.

Natural England is the “government’s adviser for the natural environment in England, helping to protect England’s nature and landscapes for people to enjoy and for the services they provide. Natural England is an executive non-departmental public body, sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs.”

The Trust continued: “A trial reintroduction can only be successful with broad support across the local community the lynx live alongside, and we know there are many differing perspectives amongst you which are all critical to hear.

“In many other countries Eurasian lynx reintroduction has proven exceptionally low-conflict and wonderfully beneficial for the local communities that live alongside them, and we do sincerely hope that these cats, which thrived here for millions of years, do have the opportunity to prove they can still fit into both our ecology, and alongside local communities like those across the Kielder region.

“The decision on exactly what happens next in the process will fall to the statutory agencies, who will receive all of the accumulated study and an application for a five year trial reintroduction within the next two months.”

Turn up the vole-ume

The lynx wouldn’t be the first species reintroduced to the Kielder region.

The largest ever reintroduction of endangered water voles in the UK is underway. Source: VisitKielder.com

Last month (June 2017) the Kielder Water & Forest Park announced the much less controversial release of 700 water voles in Kielder Forest. After a 30-year absence of that species in the forest, it is the largest water vole reintroduction to one place ever undertaken in the UK.

The Kielder Water Vole Partnership released about half of the water voles in June; those from “strong populations over the border in Scotland”. The other half — “the young from voles captured in the North Pennines in late summer 2016” — is due to be released next month (August 2017).

“The aim is to restore populations of the endangered mammal in the Kielder catchment of the north Tyne with a view to their eventual spread throughout western reaches of Northumberland.”

Water voles were a common sight in UK watercourses until the 1970s and 80s, when a combination of escaped American mink (predators of water voles) and habitat loss took a severe toll on water vole populations. As result, the water vole is now absent from the majority of Northumberland’s rivers.

Featured image: Eurasian lynx in winter coat. By Tom Bech via Flickr

Related posts