Terrorism and tourism’s diabolical relationship

Ayşegül Acar, research assistant at Karabük University, Turkey, and doctoral student at Istanbul University, explores the discomfiting relationship between terrorism and tourism in this “GT” Insight.

Bombs exploding one after another, vehicles ploughing through masses of people, media coverage, and the responses of those in power; they all create tension, international conflict, disorder, and political instability.

For tourism, an industry of peace, terrorism undoubtedly does great harm. As a matter of fact, the tourism industries of countries most greatly affected by terrorism often fall flat in the aftermath of each attack; a technical knock out in boxing terms.

Today terrorism often targets tourist destinations and events. Apart from providing easy or “soft” targets, why is tourism such an attractive target for terrorists?

The media’s relationship with terrorism

The oft-cited belief that “one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter” blurs our understanding of terrorism. Even if the objectives of terrorists themselves differ from one to another, terrorist activities in general can be gathered within three basic tactical objectives:

- Publicity (to publicise a message, a voice);

- Political instability (to hurt the legitimacy of the current regime in a country); and

- Economic harm (to inflict material pressure on the public and their leaders).

While economic harm is of greatest concern to the tourism industry, it may be possible to explain modern terrorism by investigating the role of the mass media. It can be argued that the media has served to escalate the number of violent terrorist acts since the early 1970s.

Firstly, let us evaluate the four basic elements of the communication process in the context of terrorism. That is, the messenger (the terrorist), the recipient (the political target of the terrorist act), the message (the terrorist act itself involving individual or institutional victims), and the feedback (the response of the recipient).

Let us illustrate this in a scenario that we all are familiar with in the context of travel & tourism. Let’s suppose that terrorists hijack an airliner. In this case the terrorists would initiate the communication. The target of these terrorists’ message is most probably a government. The passengers in the airliner and the hijacking itself will serve as the message which is likely to contain certain requests. Should the targeted government act in accordance with the terrorists’ requests, we would expect the terrorists to consider their communication successful.

Through it all the mass media acts as an amplifier; turning up the volume on the communication; allowing many more people to hear the message than would otherwise be possible. Thus by amplifying and accelerating the spread of news, the mass media has turned terrorism into a cost-effective means of communication by those determined to convey their message by any means necessary.

This played out during the Palestinian attack on the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, which caused the death of 11 Israeli soldiers. The Olympics is a high-profile event involving the participation of not only athletes, but also political and media representatives from most of the world’s nations. The events in Munich were witnessed by nearly 800 million television viewers around the world and conveyed a message about Israel’s occupation of Palestine.

Thus, through the participation of mass media, a relationship between terrorism and travel & tourism was born. Since then the media has made terror acts become almost familiar or “common” incidents that can be encountered anytime and anywhere. The fact that terrorism is “normal” nowadays has made extraordinary security measures, particularly at airports, a permanent and acceptable part of life.

How can terrorism and tourism be related to each other?

How can there be a close relationship, a common point, between these two very different concepts; one constructive and one destructive? Exploring the relationship between terrorism and tourism will make it easier to understand why terrorists target tourists.

Terrorism and tourism both cross national boundaries, involve citizens of different countries, and benefit from travel and communication technologies. In fact, terrorists intentionally target tourists or tourism because it is an effective way for the terrorists to reach their targets. Tourists are targeted since they symbolically represent their country and target governments. The murder of a Jewish-American passenger on the Achille Lauro cruise ship, which was hijacked by Palestinians in 1985, is a demonstration of this.

In fact the process is very simple from a terrorist’s point of view. As products of dogmatic thought and the representatives and advocates of certain points of view, terrorists do not hesitate to turn to tourism areas. There they can hide in plain sight. Large groups of tourists, who speak foreign languages and are as strange and different to locals as they are to each other, provide cover for terrorists who can wander among them without raising suspicion. Presenting as tourists themselves, terrorists can shop using foreign currencies, stop and look at things, and take pictures, just as tourists do, as they scope out a target and plan their attack.

Terrorists, who want to be recognised for their political points of view, see violent acts and the publicity they bring as a means to overcome censorship or to underscore a sense of urgency. Terrorists know that to target the citizens of multiple countries will attract more media attention than if they target only locals. With the international media interest that brings, their political issue is quickly elevated into a global concern, which in turn raises questions about the legitimacy of their target government or institution. The good publicity for the terrorist is obviously very bad for tourism, which has flow-on effects to the rest of the economy.

So, if we summarize it, terrorists target tourists to accomplish their strategic goals of publicity, political instability, and economic harm.

Tourism as a trigger

Of course it is not always true to associate terrorists and terror acts with organisations with radical political views or from different countries. Sometimes tourism itself can trigger violence.

For example, let’s consider a country or region where divisive conflicts arise between those who support tourism development and those who oppose it. Ideas that tourism is responsible for the disruption of local industry and the corruption of local culture, and perceptions that tourism development does not benefit (or even harms) local people, can polarise society and trigger violence. In these cases it is important to note that those who are involved in tourism development must act sensitively and responsibly with the understanding that poorly conceived tourism can lead to bad, even violent, reactions among some people in a destination.

Furthermore, tourists themselves should be made aware that socio-economic, cultural, and communication differences between them and their hosts can cause anger and trigger violence. Tourists who, for example, show off their wealth, flagrantly disrespect local customs, or make unreasonable demands based on their own cultural expectations, may irritate local people, contribute to a build-up of anger, and cause violent or terrorist actions when this anger is expressed in a dangerous way.

The economic harms of violence against tourism

Of course, it is inevitable that violence no matter its cause or motivation, impacts economic development. Growth rates, foreign trade revenues, exports, foreign direct investments, and all other international activities of countries subject to terrorist acts are affected negatively. One of the most important sources of foreign exchange revenue for many countries is tourism, especially in developing countries where the income is very important for solving problems such as unemployment and liquidity.

It’s also worth remembering that one of the big reasons that terrorists target tourists is that if tourism is supported by the state, or if the state relies upon tourism revenues, attacks against tourism will be perceived as attacks against the state. Since the tourism sector is an important source of economic activity, terrorist attacks aimed at tourists will cause a decrease in foreign exchange revenue placing an extra economic burden on the government.

When did terror meet tourism?

Actually, I gave the answer to this question earlier. Yes, terror and tourism were painfully introduced for the first time at the Munich Olympics in 1972. Since then they have continued to meet. Let’s take a brief look at cases where terrorists have specifically targeted tourism:

As a result of the terrorist attack in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt in 1997, the tourism sector suffered an estimated $ 1 billion loss. The 700,000 people employed by the industry and close to 7 million citizens suffered economically from the attack. Occupancy rates remained depressed for about two years.

One of the most striking examples of terrorism’s impact on a country’s economy and tourism is undoubtedly the “September 11” attacks in the US in 2001 in which four airliners were hijacked and then aimed at targets including the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York as well as a “hard” target, the Pentagon. Immediately after the attacks, in addition to a decrease in the number of domestic tourists, a significant decrease in the number of foreign tourists arriving in the US between 2001 and 2004 was observed.

However, these attacks not only damaged the US economy (about US$ 105 billion), but also economic activities in other countries. In the Asia Pacific region, due to measures taken and the expenditures made in the fight against terrorism, insurance costs and the cost of doing business increased and the productivity of the regional economy slowed down.

So many more terror attacks on tourism facilities have occurred, one after the other:

- The 2002 bombing of the Kuta tourism district in Bali, Indonesia, killed 202 people and injured 209 others.

- In 2004, 31 people were killed and 159 people were wounded in the terrorist act against the Hilton hotel in Taba, Egypt.

- In 2005, 57 people lost their lives and 110 people were injured in the bombings of three major hotels, the Hyatt, Radison SAS and Days Inn, in Amman, Jordan.

- In 2005, explosions at places where tourists were concentrated in Bali, Indonesia, caused the deaths of 20 people and injuring 129 people.

- In 2005, 88 people were killed and 150 people were injured during the terrorist acts in Ghazala Gardens Hotel and Sharm elSheikh, the resort city in the southernmost point of Sinai island of Egypt.

- In 2008, more than 602 people were killed and more than 250 people were wounded in the terrorist attack on Marriott Hotel in Islamabad, Pakistan.

- … et cetera.

Has terror always been targeted at Middle East or developing countries?

Of course not. September 11 is the highest-profile example of that. In recent times especially, terrorism has also targeted tourism destinations in Europe and other developed countries.

Let’s take a brief look at some cases in Europe:

- In 2004, 191 people were killed and about 2,000 wounded in bomb attacks at three different train stations in Madrid, Spain.

- In 2005, 56 people were killed and 700 were injured as a result of a bomb attack in London, UK.

- In 2011, 77 people lost their lives and more than 200 people injured in the bomb attack in Oslo, Norway.

- In 2015, 146 people lost their lives and 379 people were injured in three separate bomb attacks carried out one after another in Paris, France.

- In 2016, 32 people were killed and 270 people were injured during bomb attacks against an airport and metro station in Brussels, Belgium.

- In 2016, 84 people were killed and 200 people were injured as a truck ploughed through crowds of Bastille Day celebrants in Nice, France.

- … et cetera.

The numbers of people who died and were injured in past and recent terrorist acts in Europe and elsewhere show the solemnity and severity of terrorist acts. Recent terrorist acts in Europe, especially in tourism regions, have seriously damaged the tourism economy. For example, the hotel occupancy rate, which was 82% a few days before the explosion in Brussels in 2016, saw a 25% drop in the week following. There was also a huge decline in flight reservations to Brussels. The aftermath of the Paris bombings in 2015 saw hotel occupancy rates fall to 67%, a loss of 15.1% over previous years and air travel cancellations skyrocket. Similarly, as a result of the explosion in London in 2016, hotel occupancy fell to 58%, a 27.7% decline.

Turkish tourism’s tussle with terror

Turkey is at the forefront of countries that have to fight against terrorism, having fought against the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) between 1973 and 1985, and it now continues to fight against the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK or Kurdistan Workers Party), which was established in 1978. In addition to the loss of more than 30,000 people’s lives in the struggle against the PKK, the Turkish economy has suffered major losses in almost every area, especially in the tourism sector.

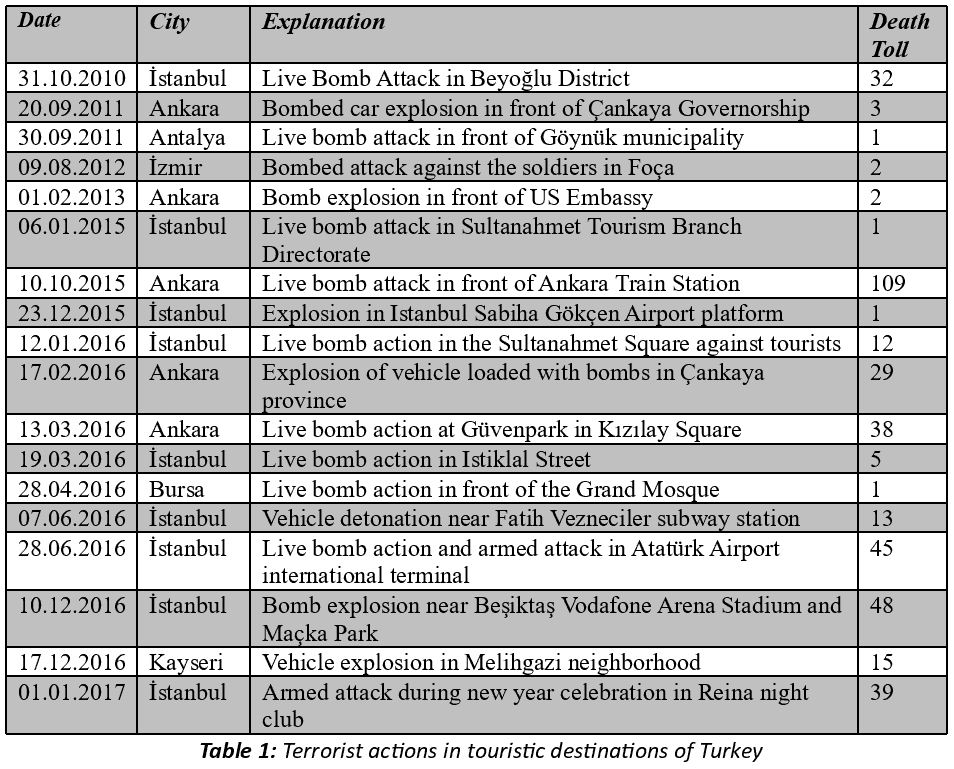

Besides the PKK’s activities, Islamic State or ISIS, which emerged in Syria and Iraq to Turkey’s south, has begun to organise terrorist acts in Turkey. The number of terrorist acts committed in Turkey over the last seven years, especially to tourists and in tourism destinations, has begun to increase considerably, as seen in table 1, especially in terms of severity and number of deaths:

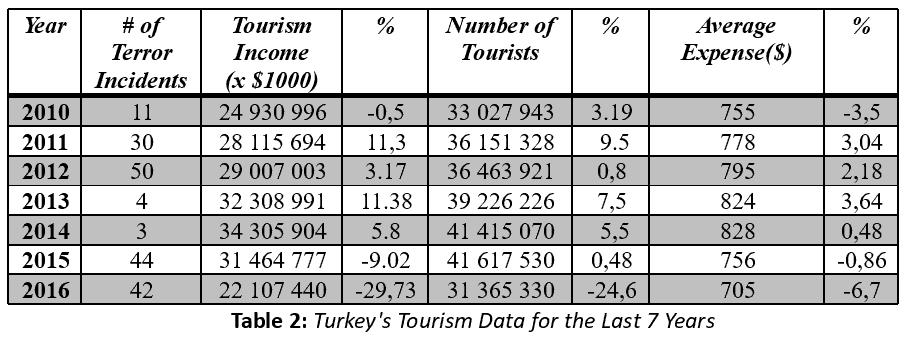

These attacks have had serious effects on tourism revenues, the number of tourists coming to the country, and the average expenditure of tourists, as presented in Table 2:

More cooperation, less conflict

Tourists are logical consumers who weigh up and decide upon products in terms of their price and performance, risk and reward. For this reason terrorist incidents in a region cause tourists to see the region as more risky. When we look at the relationship between terrorism and tourism in this way, it is clear that terrorism’s effects on tourism cannot be underestimated, and that the only way to remove these effects it to eliminate terrorism.

Although terrorism cannot be abolished at this time, measures and precautions can be taken at national and international levels to mitigate against potential risks and emergencies that may be encountered in the tourism sector. Nations that are frequently exposed to and struggle against terrorism should make every effort to cooperate. They should support a common definition of terrorism accepted by all states; cut support for states that in turn support terrorism; promote social peace, social justice and democracy in their countries; develop marketing strategies, price promotions, and package tours to boost domestic tourism; and launch various promotional campaigns to improve the country’s image internationally.

Author’s note: Readers will be provided sources individually if requested.

About the author

Ayşegül Acar completed her undergraduate studies in tourism management at Boğaziçi University, Turkey before completing her Master’s degree at Istanbul University in 2016. Ayşegül is pursuing her Ph.D. at Istanbul University while simultaneously undertaking a second Master’s with the Economics Department at Middle East Technical University and working as Research Assistant in the Department of Tourism Management, Faculty of Tourism, at Karabük University! Ayşegül’s research interests are the topics of terrorism and tourism, political instability and tourism, sustainable tourism, as well as tourism accounting and finance.